This was the story that started the Sourdough and Other Stories collection, but in a strange and wandering way. At the end of my MA, I was sending off queries letters to small publishers to see if I could interest anyone in a short story collection. What I know now is that very few publishers, large or small, will take a chance on a no-name newbie, and that’s understandable.

This was the story that started the Sourdough and Other Stories collection, but in a strange and wandering way. At the end of my MA, I was sending off queries letters to small publishers to see if I could interest anyone in a short story collection. What I know now is that very few publishers, large or small, will take a chance on a no-name newbie, and that’s understandable.

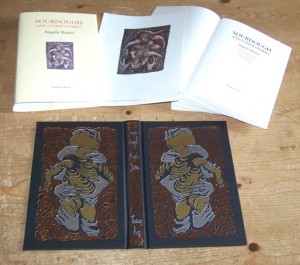

Fortunately for me, one of the publishers I sent a letter and a few sample stories to was Tartarus Press. Even more fortunately for me, the divine Rosalie Parker read the letter and the stories. She said ‘no’ to the collection, but asked if I would mind if she took the short story “Sourdough” for the next Tartarus anthology, Strange Tales II. As if I’d mind! So, my first accidental sale. That was in 2006.

In 2009 when I was writing more and the Sourdough collection was starting to take shape in my mind, I wrote to Rosalie again and asked if she’d be interested in seeing a collection of stories in that world (she’d also taken another tale for Strange Tales III, “Sister, Sister”). She was indeed interested!

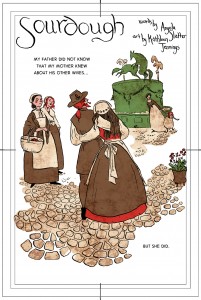

So, “Sourdough the Short” was the start of it all. I had an idea about a girl who made bread into works of art; I thought about the fairy tale “Donkeyskin”, where the princess puts her jewellery into food baked for the prince and I thought about what a silly, dangerous act that was. I’d read Margo Lanagan’s tale “Wooden Bride” and the city she described there gave me an oblique inspiration for Lodellan. I chose the name Emmeline for my protagonist because it means labourer and she does indeed labour over the making and baking of her bread creations, and I chose Peregrine as the name for her lover, because it means both a pilgrim and a wanderer, and in this story he does indeed wander for a time. And Sourdough is the story I chose as a project with Kathleen Jennings, to turn the tale into a graphic story.

Sourdough [extract]

Art by Kathleen Jennings

My father did not know that my mother knew about his other wives, but she did.

It didn’t seem to bother her, perhaps because, of them all, she had the greater independence and a measure of prosperity that was all her own. Perhaps that’s why he loved her best. Mother baked very fine bread, black and brown for the poor and shining white for the affluent. We were by no means rich, but we had more than those around us, and there was enough money spare for occasional gifts: a book for George, a toy train for Artor, and a thin silver ring for me, engraved with flowers and vines.

The sight of other children in other squares, with Father’s uniquely gleaming red hair, did not bother Mother at all. After he died, I think she found it comforting, to be reminded of him by all those bright little heads.

Our home was in one of the squares at the edge of the merchants’ quarter – the town was divided into ‘quarters’ that weren’t really quarters. Seen from above, the town.

It was a large square, made up of groups of much smaller squares (tall houses built around a common courtyard); in the centre of the town was the Cathedral, high up on a hill, then spreading around it in an orderly fashion were rows and rows of city blocks, the richest ones nearest the Cathedral, then the further out you got, the poorer the blocks. We sat just before the poorest houses, not quite good enough to be in the middle of the merchants’ rows, but still not in among the places were rats shared cradles with babies. We had several large rooms mid-way up one of the tall houses, and Mother leased out the big ground-floor kitchen for her business.

From the time I could walk I would follow Mother around the kitchen, learning her art. For a while she was simply annoyed by my constant presence, as I got under foot, but when I learnt to sit on the bench next to the huge wooden table on which she kneaded the bread, and be quiet, she decided to share her knowledge. I was her firstborn, after all, and her only daughter.

When I could see over the top of the table, I started to help her. Baking tiny child’s loaves at first for practice, much to Mother’s amusement, then making the dark, ‘poor’ bread for those who could not afford refined flour. Finally, I was allowed to create white bread to grace the tables of the rich: those born to wealth and knowing nothing else, the higher merchants, the bishop and his like. I began to create complicated twists of dough to look like artworks. At first Mother laughed, but the orders kept coming for them, so she watched and imitated me.

One morning, after we’d finished baking for the day, I began to play with the leftover dough on the board in front of me. Soon a child formed, a baby perfectly copied to the life, with tiny hands and feet, an angel’s smile and a sculpted lick of hair on its forehead.

Mother came up behind me and stared. She reached past me and squashed her fists down on the dough-child, pushing and kneading until it was once again a featureless lump.

‘Never do that. Never make an image of a person or a child. They bring bad luck, Emmeline, or things you don’t want. We don’t need any of that.’

I should have remembered the dough-child, but memory is a traitor to good sense.

*

Art by Kathleen Jennings

There was to be a wedding, arranged, a fine society ‘do’ and we were to supply the bread.

The parents of the groom – or rather, his mother – insisted on being involved in every decision pertaining to the wedding, so there was a power struggle in train between her and the bride’s mother (two titans in boned bodices). Things were getting tense, apparently – this information we had from Madame Fifine (about as French as Yorkshire pudding), the confectioner who was to supply the bonbons for the wedding feast. We were to appear at the groom’s parents’ house, goods in tow, to show our wares.

Mother and I tidied ourselves as well as we could, pulling flour-free dresses from chests and piling our hair high. Artor and George were press-ganged into carrying the wooden trays of our finest white breads to the big house near the Cathedral. We were shown into a drawing room almost as big as our ground-floor kitchen.

As soon as the boys gingerly laid the trays on the big table, Mother shooed them out. I knew they’d be in the stableyard, bumming cigarillos from the stable and kitchen lads, eyeing the horses longingly, waiting for the day when Mother could afford a horse and carriage (that day was a long way off, but they hoped the proceeds from the wedding would speed up the process).

The drawing room was awash with boredom. The parents sat stiffly across from each other on heavily embroidered chairs whose legs were so finely carved it seemed that they should not be able to support the weight of anyone, let alone these four who almost dripped with the fat of their prosperity. The bride, conversely, was thin as a twig, nervous and sallow, but pretty, with darting dark eyes and tightly pulled hair sitting in a thick, dark red bun at the base of her neck. The groom did not face the room: he had removed himself to the large French window and was staring at the courtyard below (probably watching my brothers watching his horses). He had dark hair, curly, that kissed the collar of his jacket, and he was tall but that was all I could tell. Madame Fifine had said he was called Peregrine.

Mother nodded to me and I took the first loaf from one of the trays, showed it to the clients so they could observe its clever shape (a church bell with bows), then placed it on a platter and cut six slices for them to taste. The two mothers, the two fathers, the bride all took their slices and the room was silent but for their well-bred chewing. I crossed the room and offered the groom the last slice. He didn’t turn, merely raised his hand in a ‘no’ and shook his head. I noticed his hand bore the stain of a port-wine birthmark.

‘It would be a shame, sir, to waste something so fine.’

Perhaps struck by the fact that I spoke to him, he looked at me and broke into a smile.

‘Yes. You’re right. It would be a shame.’ He took the bread, green eyes bright. ‘What hair you have, miss.’

I blushed.

‘Emmeline.’ Mother called me and I began my task over again: now the loaf shaped like a flower, now the one like an angel, now all the animal shapes (rabbits, doves, kittens, a horse), the one like a church. Each time I saved his slice until last and we spoke in low voices, he asked me about my life and laughed at my pert answers. When the tasting was finished, the mothers began to argue; the design to choose was the cause of combat. Finally, they turned to the girl, Sylvia, and made her decide. She had the look of a trapped animal and I felt sorry for her.

‘Perhaps…’ I began and all eyes turned to me, the mothers’ brimming with affront, the fathers’ with boredom, the groom’s with amusement, my own mother’s with something like dread, and the bride’s with hope of rescue. ‘Perhaps Miss Sylvia has a favourite animal or flower. We could make the bread to her choice if she does not like what we have brought today.’

‘A fox!’ she cried, clapping her hands to her mouth as if she had said something a-wrong or too bold. I smiled and she said more firmly. ‘Yes, a fox. That would please me.’

‘As you wish, Miss Sylvia.’ Mother’s voice was a relieved breeze. ‘My Emmeline can make anything with her hands; she has great skill.’

So it was settled. The bride had spoken, and defied both her mother and future mother-in-law. Mother and I hefted the wooden trays scattered with the remains of butchered loaves and made for the door. The groom was there before the footman and ushered us through. He smiled and I felt as warm as bread fresh from the oven.

***

?