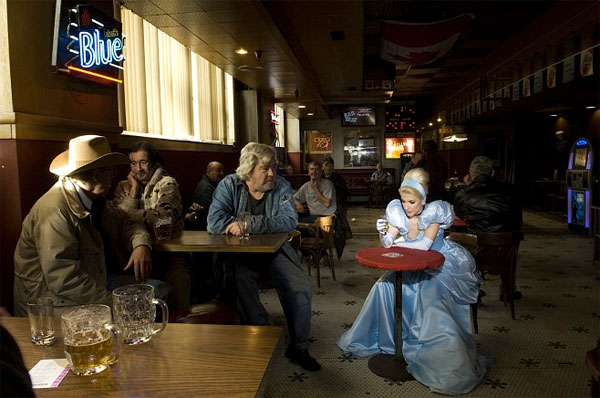

This is a little something extracted from my Masters thesis, Black-Winged Angels: Theoretical Underpinnings (which is a collection of nine reloaded fairytales and an accompanying exegesis). It’s just lying around, so why not post it here? Complete with dodgy bibliography and endnotes. Some of it appeared here already. Also, these images are from the amazing Dina Goldstein’s series, Fallen Princesses, which lives here.

This is a little something extracted from my Masters thesis, Black-Winged Angels: Theoretical Underpinnings (which is a collection of nine reloaded fairytales and an accompanying exegesis). It’s just lying around, so why not post it here? Complete with dodgy bibliography and endnotes. Some of it appeared here already. Also, these images are from the amazing Dina Goldstein’s series, Fallen Princesses, which lives here.

The Chosen Girl

At the end of the fairytale, at the happily-ever-after end, there is invariably one girl left standing. She has come through a variety of trials set for her by fate and has triumphed by winning the heart of the prince. More often than not, she has won the competition to be chosen. She will generally have been one of a pair : a pair of sisters (full or step), the mother-daughter pair (again, full or step), aunt-niece, childhood friends, etcetera. Inevitably, there is a future up for grabs and, if we take the wisdom of Highlander to heart, in the end there can be only one. So, who is – what is – the ‘chosen girl’ and how does one become her?

First Fairy Tales

The translation of fairy tales from oral to written form brought with it a change in the messages the tales were to transmit. From stories simply meant to teach members of the tribe about life and death, they became a means of socialising young girls. The original oral tradition reflected customs, beliefs and rituals, and were stories told for adults as well as children[i]. Noted folklorist Jack Zipes described such tales as “marks that leave traces of the human struggle for immortality”[ii], but they are also a means of acculturation and present ways of teaching and learning behaviours, value systems, and consequences [iii]. Male writers/transcribers such as Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm took these tales from a variety of women, old and young, collected them and wrote them down. They did not, however, simply copy the tales verbatim, but rather changed them to suit their own purposes. The tales were transformed, the voice colonised. Essentially they became stories to teach little girls how to behave and were used to fulfil a controlling and socialising function: they were lessons in how to be a ‘chosen girl’.

When tales began to be set down in written form in the sixteenth century, they were not especially suitable for children – the collections of both Basile and Straparola are filled with illicit sex, bawdy tales and amusements generally not meant for any child’s bedtime reading[iv]. Subsequently, in the salons of seventeenth and eighteenth century France, the literary fairy tale became popular and, for a time, had an adult upper class audience. Gradually, though, there was a shift, which led to the fairy tale being regarded as the province of children. Zipes points to a convergence of the budding middle class, an increase in literacy, and the nascent idea of children as “innocent and educable”[v] leading to fairy tales being told almost exclusively to children in nurseries.

The recounting of fairy tales had traditionally been associated with women[vi], yet it became, in some ways, a tool of oppression and subjugation. Deszcz notes that the genre became aligned “with patriarchal cultural practices in Western societies”[vii], the child’s tale used to transmit messages that “sustain gendered perspectives”[viii].

Perrault operated in the salons of France in the mid-late seventeenth century, and although he was by no means the only ‘recorder’ of tales – female authors outnumbered the males working in the genre[ix] at the time – it is his versions that survived and dominated the Western fairy tale tradition. The works of his contemporary female authors such as Marie-Jeanne L’Heritier, Marie-Catherine d’Aulonoy, Gabrielle-Suzanne de Villeneuve, and Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont, all of whom championed the cause of independence for women in their written works, are largely forgotten[x].

Although he claimed to be “a mere conduit of past wisdom”[xi] (not creating stories but simply taking the tales from a “pristine source”[xii]), (nurses, gouvernantes, grandmothers, random old female gossips), Perrault did not leave the tales virgo intacto. He changed them, transformed them to suit his own purposes – Marina Warner notes that he “set aside aspects which struck him as crude”[xiii] and Zipes, in relation to Perrault’s version of Little Red Riding Hood[xiv], points out that the author’s “[own] fear of women and his own sexual drives are incorporated into his new literary version, which also reflects general male attitudes about women portrayed as eager to be seduced or raped”[xv].

Perrault’s tales became moralizing stories, warning women and children that if they did not conform they would have to deal with consequences. The fact of his enduring popularity [xvi] at the expense of equally well-written and amusing tales by contemporary females, suggest that the stories and their acculturation function were seen as useful.

A Woman’s Place in Fairy Tales

Fairy tales, those most widely disseminated by children’s fairy tale collections such as the Brothers Grimm and read at bedtime, show a picture of how little girls should be – socialisation beginning in the cradle. Good girls, we are told, are silent and submissive, their value is their beauty and their fertility. Good girls are rewarded with marriage; the bad girls (those who talk back, think independently and don’t wait for the prince), are punished. In order to become the chosen girl one must follow a preordained pattern.

M K Lieberman notes the primacy of beauty in fairy tales – children are taught that the beautiful girls are the best, the sweetest, the most interesting – the ones who will be rewarded[xvii]. The homely, it seems, are in serious trouble and a good personality is no kind of saving grace for a girl. Boys can be as ordinary as can be (even downright ugly or not even human) and someone will always want to marry them (for example Hans My Hedgehog, King Thrushbeard, Dummling). The upshot of being beautiful is the assumption that you will be chosen – as Lieberman observes “The beautiful girl does not have to do anything to merit being chosen; she does not have to show pluck, resourcefulness, or wit; she is chosen because she is beautiful”[xviii]. With beauty comes passivity – Gilbert and Gubar make the wonderful observation that Snow White, as she lies in her glass coffin, for all purposes lifeless, has become “the chaste maiden in her passivity, they have made her precisely into the eternally beautiful, inanimate objet d’art patriarchal aesthetics want a girl to be”[xix]. Judgments about activity are sex-linked – passivity is for girls, activity is for boys[xx].

The very occasional ugly, active girl in fairy tales has to work much harder: in Shaggy Top (also known as Tatterhood) the title character is ugly but resourceful and extremely brave and active, protecting and rescuing her passive, victimised (very beautiful) sister, and ultimately being rewarded with beauty and a princely husband. In Green Serpent the main character, Laidronette, is also born ugly and is judged by her looks not her sweet nature – ultimately though, she too is rewarded with beauty and a handsome prince.

On the whole, however, in fairy tales women who are ugly are old, witches, ogresses, power-hungry, unnatural, unwomanly, active, wicked, non-conforming, demanding, questioning and disobedient – in short, pushy. The only real exception to this established dichotomy is the fairy godmother – she is powerful and often beautiful – but then, she isn’t real. A real girl cannot hope to become a “fairy”[xxi], all she can aspire to is to be a beautiful, passive, chosen girl.

Another key virtue for the girl who aspires to be a fairy tale princess is, if not complete silence, then at least gentle speech. King Lear lauds his dead Cordelia with “Her voice was ever soft, gentle, and low, an excellent thing in woman”[xxii]. Warner notes that silence could be a survival mechanism for women – saying nothing meant you offended no one. The problem with survival through silence is that it means you have no voice at all.

Regarding silence as a virtue to which women were taught to aspire also meant a disinclination to dissent for fear of being thought “unwomanly”. Both Warner and Blackwell discuss Ruth Bottigheimer’s quantitative survey on the speech patterns of women in the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm. The tales collected by the brothers came directly from the oral tradition, from a variety of women who lived around them. The Grimms’ fairy tale collections went through several editions over the space of approximately seven years and across these editions changes were made: ‘good’ girls speak less and less from edition to edition; silence as a task for men lasts up to three days, for women it is often seven years; the female voice is frequently taken away from her, whereas the male willingly stops speaking; girls speak when spoken to and generally do not ask questions unless invited; and perhaps most tellingly, those who speak most are witches (i.e. bad women who don’t conform) and boys (in whom activity and curiosity are lauded) [xxiii]. The editing out of female speech in fairy tales by male authors/ transcribers shows in a very real way how tales have been used as a means of training women how to behave in a socially (i.e. patriarchally) accepted fashion.

Blackwell observed that in Germany the phenomenon of young mothers reading to their children from the new books of “sanctioned” Grimms’ tales replaced the oral tradition of fairy tale telling in the evening. Old women – nurses, grandmothers and the like – were suspect as tellers of tales; they were the kind of old wives who would change the stories, who would improvise, and who would not conform[xxiv]. The power of the tale for the patriarchy lay in its static nature – the pattern did not change, the end did not change, girls stayed girls and boys, boys. If women tellers changed the stories, they were behaving independently and independent female action was to be feared[xxv].

This process, Blackwell notes, removes “Authority … from the oral female voice to the male editor/ author, but returned to her in a sanitized form, when she is the properly behaving dispenser of his tale”[xxvi]. The voice of the mother was used to enforce ideas of sanctioned behaviour: girls are quiet, pretty, submissive and are there to be rescued. Imagine the power of co-opted maternal voices enforcing the edicts of the ruling order. The hand that rocked the cradle worked for the other side, as models of and conduits for female behaviour women were complicit in the subjugation of their own daughters[xxvii]. Mothers now told their daughters through the medium of bedtime stories “I have no value beyond beauty, silence and fertility. My daughter, you are like me. My son, you are not like me, you are special!”

Fairy tales also teach girls about reward and punishment – those who conform are rewarded, those who do not are punished, ridiculed and subjugated, or worse, killed. The ultimate reward for good girls in fairy tales is marriage – if a girl is beautiful, passive, submissive, silent, and helpless then even if she is poor, she will get her man – or rather, he will get her. Marriage for fairy tale girls also means a step up the social ladder and access to wealth[xxviii].

Fairy tales end with marriages – Lieberman states that fairy tales are “preoccupied with marriage without portraying it; as a real condition, it’s nearly always off-stage”[xxix]. Indeed, in the main the only marriages shown are bad ones, or sad ones, in which the queen suffers a cruel husband (Bluebeard) or is about to die (Snow White, Donekyskin). Marriage in fairy tales remains a kind of happily-never-after.

Those who refuse marriage are punished for being ‘unnatural’ – the princess in The Yellow Dwarf initially refuses suitors so her father marries her to a dwarf, she then falls in love with a young man whom the dwarf, in a fit of jealousy, kills and the princess herself dies of a broken heart[xxx]. Similarly in King Thrushbeard a proud princess rejects suitor after suitor and her father marries her to a pauper who proceeds to humiliate her at every opportunity until he finally reveals himself as one of the original scorned suitors who felt it his duty to break her down and make her a proper wife[xxxi].

In addition, chosen girls don’t help. A study by Mendelson highlights the lack of collaboration between women in the Grimms’ fairy tales. He notes that whilst men frequently band together to help each other in the achievement of a goal (treasure, etcetera), women tend to be denied this option[xxxii]. While there are often one-on-one relationships for women (fairy godmothers, faithful servants, the very occasional helpful sister, or mother’s ghost) on the whole any larger group of women is regarded as suspect – a coven of sorts[xxxiii]. Perhaps one of the reasons for this is the fear men have of women in groups – “[female] collaboration is tantamount to corruption, devoutly to be feared as an agent of destruction rather than praised as a means of support and empowerment”[xxxiv].

In addition to this, the ‘prize’ for a female is always a prince, always marriage – only one girl can win – in fairy tales, particularly Russian ones, men can win more than one bride. The competition for male attention and protection set up in fairy tales, “that marriage is the only estate toward which women should aspire”[xxxv], is enough to cause a schism between females vying for the same prize. Not only that, marriage is the state which is upheld by society as the desired state of being, the much lauded conformity for which women must strive – within marriage lies sanctioned sexual relations, children (proof of a woman’s fertility), and the protection of a male[xxxvi].

Messages

Karen Rowe notes that “subconsciously women may transfer from fairy tales into real life cultural norms which exalt passivity, dependency, and self-sacrifice as a female’s cardinal virtues. In short, fairy tales perpetuate the patriarchal status quo by making female subordination seem a romantically desirable, indeed an inescapable fate”[xxxvii].

It is easy to see fairy tales simply as ‘kids’ stories’ and to dismiss them, but viewing them closely shows they are actually powerful, multi-layered acculturation tools. As writers such as Rowe have observed “… such alluring fantasies gloss over the heroine’s ability to act self-assertively, total reliance on external rescues, willing bondage to father and prince, and her restriction to hearth and nursery”[xxxviii]. Assuming fairy tales are just stories ensures that women will keep “assimilating cultural imperatives”[xxxix], such as be quiet, be pretty, be submissive, your highest goal is marriage and motherhood, expect no more. Passing this onto our daughters and our sons enforces the idea that daughters should be silent, pretty and still and that boys have a right to expect them to be so – that women should be less than they can be in order to keep the status quo, and as Rowe puts it “the harmonious continuity of civilisation will be assured”[xl].

Traditionally, when tales were told in the old way, when they were spoken, they tended to end with the words “This is my story, I’ve told it, and in your hands I leave it”[xli], which recognises the communal nature of the stories and of their authorship, over time and in different contexts. It also tells us that we should tell our children the stories from which we want them to learn – that both girls and boys should be taught to be bold and brave, to make their own fates and not to simply expect them.

Bibliography

Blackwell, J. (2001) “Fractured Fairy Tales: German Women Authors and the Grimm Tradition”, The Germanic Review, pp. 162-174.

Deszcz, J. (2004) “Salman Rushdie’s Attempt at a Feminist Fairytale Reconfiguration in Shame”, Folklore, 115 (1): 27, pp.27-44.

Gilbert, S. M. and Gubar, S. (1979) “The Queen’s Looking Glass”, in Zipes, J. (1986) Don’t Bet on the Prince: Contemporary Feminist Fairy Tales in North America and England, Aldershot, England: Gower, pp. 201-208.

Lieberman, M. K. (1986) “’Some Day My Prince Will Come’: Female Acculturation through the Fairy Tale”, in Zipes, J. (1986) Don’t Bet on the Prince: Contemporary Feminist Fairy Tales in North America and England, Aldershot, England: Gower, pp. 185-200.

Mendelson, M. (1997) “Forever Acting Alone: The Absence of Female Collaboration in Grimms’ Fairy Tales”, Children’s Literature in Education, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 111-125.

Rowe, K. E. (1979) “Feminism and Fairy Tales”, in Zipes, J. (1986) Don’t Bet on the Prince: Contemporary Feminist Fairy Tales in North America and England, Aldershot, England: Gower, pp. 209-226.

Slatter, Angela. (2008) “Little Red Riding Hood: Life off the Path”, Apex Science Fiction and Horror Digest, Volume 1, Issue 12.

Warner, M. (1995) From the Beast to the Blonde: on Fairy Tales and Their Tellers. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Warner, M. (1990) “Mother Goose Tales: Female Fiction, Female Fact?”, Folklore, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 3-25

Warner, M. (1991) “The Absent Mother”, History Today, Vol. 41, Iss. 4, pp. 22-29.

Windling, T. (1997) Women and Fairy Tales, www.endicott-studio.com/rdrm/forwmnft.html, retrieved 7/05/2005.

Zipes, J. (1986) Don’t Bet on the Prince: Contemporary Feminist Fairy Tales in North America and England, Aldershot, England: Gower.

Zipes, J. (1994) Fairy Tale As Myth/Myth As Fairy Tale. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

Zipes, J. (1983) Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion. London: Heinemann.

Zipes, J. (ed) (1992) Spells of Enchantment: The Wondrous Fairy Tales of Western Culture. New York: Penguin Books.

[i] Zipes, 1992, p. xii

[ii] Zipes, 1992, p. xii

[iii] Lieberman, 1986, p. 187

[iv] Windling, n.d., p. 6

[v] Blackwell, 2001, p. 163

[vi] Warner, 1995, p. 23

[vii] Deszcz , 2004, p. 27

[viii] Deszcz , 2004, p. 27

[ix] Windling, n.d., p. 2

[x] Warner, 1991, p. 22

[xi] Warner, 1990, p. 4

[xii] Warner, 1990, p. 4

[xiii] Warner, 1995, 181

[xiv] An article detailing the journey of LRRH appears in Apex Science Fiction and Horror Digest, Volume 1, Issue 12, 2008.

[xv] Zipes, 1986, p. 229

[xvi] Zipes, 1986, p. 227

[xvii] Lieberman, 1986, p.188

[xviii] Lieberman, 1986, p. 188

[xix] Gilbert & Gubar, 1986, p. 204

[xx] Lieberman, 1986, p. 197

[xxi] Lieberman, 1986, p. 197

[xxii] Warner, 1995, p. 389

[xxiii] Blackwell, 2001, p. 164

[xxiv] Blackwell, 2001, p. 165

[xxv] Blackwell, 2001, p. 165

[xxvi] Blackwell, 2001, p.165

[xxvii] Rowe, 1986, p. 214

[xxviii] Rowe, 1986, p. 217

[xxix] Lieberman, 1986, p. 199

[xxx] Lieberman, 1986, p. 198

[xxxi] Lieberman, 1986, p. 198

[xxxii] Mendelson, 1997, p. 111

[xxxiii] Mendelson, 1997, p. 115

[xxxiv] Mendelson, 1997, p. 118

[xxxv] Rowe, 1986, p. 211

[xxxvi] Rowe, 1986, pp. 220-1

[xxxvii] Rowe, 1986, p. 209

[xxxviii] Rowe, 1986, p. 209

[xxxix] Rowe, 1986, p. 211

[xl] Rowe, 1986, p. 221

[xli] Warner, 1995, p. XXV

8 Responses to The Chosen Girl – Happily Never After