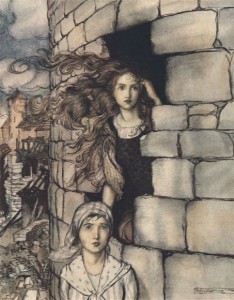

Rackham’s Maid Maleen

This was a really challenging story to write because I’d had the scene of spinning hair and making a tapestry from a body in my head for a couple of years before I wrote the full tale. I’d done a very early version of it when I was still a very new writer (at the start of my MA) and knew that it was, at that stage, beyond the reach of my talent. So, I had to hang onto it until I was a much better writer, until I could do it justice.

The title came from a line of a poem I’d heard read ages ago at a VoiceWorks event; a poem about immigration and memory. I thought it an exquisite phrase and have also used it for the name of this blog.

Of course, when I finally got around to writing the story to fit into the Sourdough mosaic, it was still difficult to write. I was pleased with myself at the end: I’d managed to work in both the fate of Dibblespin’s sister Ingrid, and the back story of Rilka, a nun and the Marshall of a Battle Abbey of the Church Militant who appears later in “Sister, Sister”, and allowed Ella from “The Shadow Tree” to ghost through like a dark presence, and referenced the tower from “Little Radish”. I’d woven in the tale of the great and terrible making of the bodily tapestry. I was pleased … but I wasn’t entirely sure it worked; it felt untidy, ragged at its edges.

Feedback from Lisa confirmed my suspicions, and resulted in one of the biggest eviscerations I’ve ever done of a story. A terrifying and ambitious process, to cast aside all preconceptions of what you think the story was/is/should be and remake it, turning the tale into a kind of wordish Frankenstein’s monster. And at the end of it all, the gratifying response from my alpha reader that now, all was well.

It’s a tale about blood and families, sisters and loss, about stories within stories, about bones and babies and the prick of a thorn.

The Bones Remember Everything

I walked for three days.

I had not left a note for Rilka, left her no clue; I had not thought of my lover when I entered the woods. The wolves were shadows and did not bother me. Need for neither food nor drink slowed my progress. There was only the voice, which no longer simply inhabited my dreams, but hummed through the waking hours like a daylight lullaby. I kept going until I reached the place where I was told I needed to be. Ingrid, welcome home.

The path ended abruptly at a prickly barrier; a hide of thorns so thickly grown and woven that I couldn’t make out what lay beyond. The bushes stretched as far as I could see. Left and right, the briars had melded with the usual flora, and there was no way past to be found. I reached up in frustration, to touch one of the branches, but I misjudged and snagged a finger on a long barb.

I put the digit in my mouth and sucked away the welling fluid, tasting its metallic tang. In front of me, though, the drop of blood remaining on the tip of the spike gleamed then began to eat away the brambles just as acid attacks metal. Soon, there was a wound in the wall, big enough for me to walk through. I gave one final look back to see the obstacle continuing to be erased as if it had never been.

Ravens hopped across an untamed lawn and a grey stone tower rose up in the middle of the clearing. Lining the crenellations were statues – not gargoyles but cats. A single door at the base stood ajar. I did not hesitate; the voice urged me on.

Inside, at the bottom was a disused kitchen; then halfway up, a library with shelf-lined

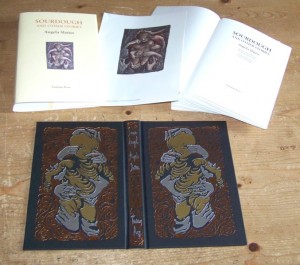

Original art by Stephen J. Clark

walls; finally at the very top of a spiral of age-smoothed stairs a circular room waited. Four arched windows, set across from each other, to the four compass points, let in light. In one area was a spinning wheel covered in cobwebs; a stool was placed in front of it. A four-poster bed crumbled quietly, its hangings all decayed, and bookshelves had been picked bare by birds and mice looking to cushion nests. Only a tiny cat and raven, cleverly carved in stone, lay over-turned on the splintered wood. Against another part of the wall hung a frame made of bones; stretched across it was a covering of skin. At its foot stood a rough-hewn table and on that table were thread, a needle, a quill and a very large jar – almost a glass pail, really. At first, I thought it filled with ink, but closer inspection showed it to be a sluggish dark red, uncongealed. The lid came away with surprising ease. The scent of iron made me dizzy.

The very air seemed to be waiting

The quill was sharp, and when I picked it up, I felt a tingle in my hand that thrummed up my arm and made my shoulder ache. I dipped the nib into the ichor-ink and stood in front of the strange canvas. I swiftly sketched a woman, the one whose voice sang from my dreams. Without knowledge I understood that she shared my blood. The liquid soaked straight into the surface, did not run or smear; it knew where it was to stay.

When the drawing was done, I waited for the outline of the face and body to dry. I picked about the chamber, trying to find a trail, a story in the leftovers of a life. There was little enough and I realised that the only truth was that of the bones.

I closed my eyes and saw a girl sitting by a window, the north-facing window of that very tower, spinning. The thread her efforts produced was long and fine, flax entwined with strands of her own dark hair—she had been at the work for some time. Every so often she pricked her finger and the crimson welled, then was absorbed into the filaments as she caressed them with something like love, something like hate. The pain didn’t bother her, for she was spinning her own life, making herself into a tale, her own tale of blood and flesh and bone, and she would endure for the bones remember everything. And they will call.

I shook myself and opened my eyes. The fine silver needle was surprisingly easy to thread. As I sewed and embroidered, the fibres took on the required colour: ebony for hair, white as new snow for skin, red as a ripe apple for lips. I stitched and stitched, and wondered what would happen when I finished.

Still I did not sleep; day and night no longer mattered. I did not mind, though, for the voice called me by my name and told me its story.

***