I’m very fond of this story – I wrote it at Clarion South and after it had seven shades of brown kicked out of it during the crit session, Jack Dann, who was our pack leader for week five said “If I was looking for stories for an anthology right now, I would buy this story.” Understandably, I am also very fond of Jack Dann.

I’m very fond of this story – I wrote it at Clarion South and after it had seven shades of brown kicked out of it during the crit session, Jack Dann, who was our pack leader for week five said “If I was looking for stories for an anthology right now, I would buy this story.” Understandably, I am also very fond of Jack Dann.

The story began with the image of a man with wings, soaring up into the blue sky above a calm sea. In the final draft the perspective changed as I realised it was a recounted tale from someone else’s point of view: that of the nameless narrator. She’d loved Windeyer, the Navigator, one of the last of his kind, winged men who kept ships on course due to their avian instincts. But the Navigators were essentially slaves, kept on ships, not employed on them. Windeyer, whose wings were taken from him, had found a way to get them back and there was nothing he wouldn’t give in exchange.

The female narrator loves him, but she’s also the daughter of the man who maimed Windeyer; she carries her guilt around tightly entwined with her love. Her father was a man called Balthazar Cotton, who appeared briefly in “Gallowberries” – and who also appears in my Tor.com novella, Of Sorrow and Such (due in October 2015) – and the sense I had of her was that her life had shrunk. Her parents were gone, her shipping empire had been whittled away gradually, and Windeyer no longer loved her as much as he loved his obsession with getting his wings back. And as things and people were subtracted from her life, nothing came to replace them, so the emptiness grew.

An important thing for me with this tale is the ending: I wanted to leave a sense of unknowing, of a continuation of the story after the last full stop. To leave the reader forever caught between was she saved or wasn’t she? Coz I’m cruel like that.

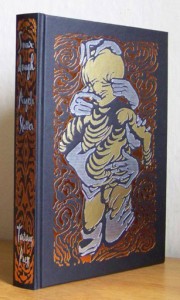

The Navigator

Windeyer perches atop the mast, face to the wind, eyes (all pupils) unblinking. His shoulders twitch as if the stumps of his wings itch and ache. Some days, when he’s aloft like this, I think I can see the sun shine through him, his bones a dark frame beneath his skin. Perhaps I imagine it. He should have been able to fly; they should have left him that.

Not many ships have Navigators such as he anymore; his kind began dying out twenty years ago. Pining, avian-human diseases, masters who got sick of having to retrieve runaways and, in frustration, transected them with a crossbow bolt. It was, I think, a kind of mass suicide, a tribal loss of the will to live. With their wings taken, with no freedom, what was the point?

He moves and I tense. In a fluid movement he dives from the mast, from the very top, into the sea. I watch, fearful that he won’t come up, will founder like his father. That he will drink in the sea instead of the air and chose to sleep on the sandy bottom. At last, he surfaces.

I do not chide him. His cruelties are few and this is the worst of them: to endanger himself in front of me. Some days he won’t talk. I feel, more and more, this distance between us, his lack of wings and mine.

‘How much longer?’ I ask as he hauls himself over the ship’s rails. I’m relieved to see he doesn’t consult the map. It’s drawn on human skin and I do not wish to think on how he came by it. He reaches out and runs his fingers down my face, leaving salt and water there, writing my tears for me.

‘Another day, another night. Afraid?’

I shake my head.

‘It’s not too late,’ he says. ‘We can still turn back. You can marry your way out of poverty.’

‘Or I can sell you. That would clear all debts.’

It hangs between us, bitter fruit. I turn away and fix my eyes on the endless horizon. The wheel under my hand is sweet.

*

Windeyer was sired on a human whore by my father’s navigator, Desidero. The woman

(c) Manchester City Galleries; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

had waited for a year until the North Star returned to port and then presented the surprised sire with a babe in arms, whose metre-wide wing-span took one’s breath away. She demanded money in exchange for her son. Desidero begged my father to buy the boy.

Desidero was wild, his wings clipped late, but he found some bond with my father and stayed. Behaved abominably but stayed. It must have been something more than a shared interest in whoring that kept them together, must have been a kind of friendship, for in spite of his wildness, Desidero never tried to run. He loved the ship and he loved my father. Perhaps it would have been better for him to flee for he died in a storm when his son was five.

I was born six years after Windeyer. Mother was a fine lady of good family who’d married my merchant father and expired with the shock of giving birth to me. Balthazar Cotton didn’t entrust me to a governess as a proper father should: I was carried around in a small woven cocoon, hung on the nearest mast when he needed both hands free, always carefully shielded from the sun. My father, born in a landlocked city, discovered late in life that he loved the sea; I was born to it. So much time did I spend at sea that solid land always felt foreign to me. The inland air I breathed when Father took me on visits to his birthplace of Briarton, was free of salt and soak; it tasted wrong.

Windeyer was given guardianship of me – to teach him responsibility my father said – and he looked after me as well as a brother might. In those early years his wings had not been taken and he would sweep me up and we would fly above the ocean as the ship floated beneath us. This was his gift to me: to know what it was like to soar on the thermal currents, to see things the way the gods do, to feel unbounded by earth and dirt and gravity.

And I took that from him.

*

The night air is clean, salty. I breathe it deep and hold it in my lungs as long as I can; as if every breath counts. We are anchored outside the reef surrounding the island of the Sirens. I would not risk the passage in darkness, so Windeyer has been forced to wait. He sulks in the bow, his back to me. I think I see the shadow his wings once cast.

‘I have a way out,’ he said not so many weeks ago. This is the only ship left in the fleet I inherited from my father: a small sloop, just barely manageable by the two of us. The others have been variously lost: storms and sea monsters; one commandeered by the Royal Navy and subsequently destroyed by pirates; and one lost in a regrettable card game for which I blame Windeyer entirely.

There is still the house, the white and iron mansion perched on the gentle hill above the port-city of Breakwater. But it is mostly emptied of furniture, all but our bed and cooking utensils for those brief times when we are at home and not scouring the sea for some kind of commerce, stopping short of piracy as much as possible. Transporting as many small cargos and paying passengers as we can to keep body and soul together. I have had to let the crew go, one by one, to ships where they are guaranteed pay.

I could, as Windeyer taunts, marry: there are several suitors, all rich and fat and well-connected. They would keep me in a sugar-spun web of boredom, leave me to learn to embroider and raise round little children, the boys replicas of their father, and the girls tiny versions of a caged mother going slowly mad.

‘Sirens’ bones,’ he said to me and might well have been a siren himself (he carries their blood, though diluted by years and generations). ‘Remember mine? Think of what pure Sirens’ bones will fetch.’

When my father ordered Windeyer clipped, he had the great black wings nailed to the main mast of the North Star. They stayed there until at last the feathers and flesh fell away and left glorious bright bones that clattered to the deck and proceeded to sing. Father had them bundled up and sold as soon as we made port. With the proceeds he bought another ship.

‘Why would the Sirens give up their bones to us, Windeyer?’ I asked.

‘We only need one set – we don’t even need a full set. We don’t need to ask. The bones will be lying about.’

‘How do you know?

‘They build wooden towers for their dead. They leave the bodies to rot. The towers fall and the bones litter the island. I read it in Murcianus.’

‘No one is allowed on the island.’

‘Pilgrims are. Navigators are. My kind are welcome.’ His eyes darkened and I couldn’t quite divine if he was bitter or pleased.

And I agreed, at last, even though I knew he had told me truth with a lie rolled up tightly inside.

***