http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Green_Man_carving.jpg

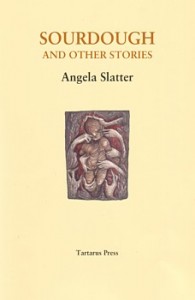

This story first appeared in the lovely Shimmer #5 in 2006 (and illustrated by a wondrous piece by Sandro Castelli). The title came from a late night episode of Frost, I think, in which there was indeed a place called the Angel Wood. I liked the idea of mixing something religious with something deeply pagan, as though the wrapping of the name would lull you into a false sense of security, then when you opened it you’d find a Green Man inside, staring back at you.

“The Angel Wood” began with the idea of people fleeing; the reason for their flight wasn’t important (although it was a plague in a big city), but where they washed up was. The critical thing was the crisis that began the short story and then the consequences of choices made in both the past and the present. I can’t tell you why, but I knew they were in a carriage, they were dressed in clothing that owed a lot of the period of Charles I of England. I knew there was a mother driven to save her children, so desperate that she took them back to the home she’d fled years earlier. So desperate that she’d finally face the things she’d done by her own desertion of her mother and uncles.

I had the main character in my head, the oldest child, Henrietta, called Henri. I knew her voice and her point of view; she was an excellent vessel for new experiences. She’s a girl who’s on the cusp of womanhood and also, suddenly, an entirely new life, but a life that is also old and inherited. She has the chance to rebuild her family, the Woodvilles, and reinvigorate the forest – and to save her mother’s life, even though that will drive a wedge between them.

Again, it was a story that was written before the Sourdough collection, but which I knew had a place in it – I used Tildy, one of the twins, in a later tale, “Lavender and Lychgates”.

The Angel Wood

We wake only when a sudden stop almost jerks us from the seat. Now, with the plague-ridden city just a memory, the air is so sweet it creeps up our nostrils and makes us sneeze at its strangeness.

Jeremy-Charles lies quiet in my arms while Milly and Tildy snuggle, one either side of me. Outside, Mother’s voice is tense as she says she carries only victims from the city. A man answers that she lies – who would bother to transport the dying so far from Breakwater? I bid my siblings be silent, and peek through the gap between the door frame and the curtains that cover the windows.

Two men sit astride fairly fine horses – surely stolen – their faces wrapped in scarves, and pistols casually aimed at my mother. I don’t think they’ve realized that she is a woman, tall as she is, dressed in Father’s clothes, her voice deep. Her red mane is caught up under a hat.

One of them ambles his mount toward the carriage. I slide one of the pistols from under my cloak and hold it in both hands, trying to steady it. When the door opens, the highwayman’s eyes widen in the moment before I fire and his face turns to red. A second shot, then a third, rings out and I fall from the conveyance. Behind me, the children scream.

The other man lies on the ground, victim to the pistol Mother carries. The third shot seems to have gone astray.

My siblings continue to howl until Mother yells at them to be quiet. As she has never raised her voice to any of us before, the shock has the desired effect.

‘Tie their horses to the back of the carriage, Henrietta. Hurry up about it.’

I do as bid with shaking hands. As I move to climb back in, my stomach heaves. The grass is soft when I fall and vomit as if my innards are trying to leave my body. Mother’s palms are cool on my forehead as she holds my hair back and strokes my face.

‘Is Henri sick, Mama?” Tildy’s voice trembles. Mother shakes her head, blue eyes warm and pitying.

‘No, Henri is not ill. She’s just upset. Get back in the carriage, Tildy.’ She helps me up, lowering her voice. ‘First things are always hardest, Henri. It will be easier next time.’

She bundles me in and shuts the door, hard. We rock under her weight as she climbs back into place. The horses start forward and I go back to sleep, curled around Jeremy-Charles, my sisters watching me cautiously from the opposite seat. My dreams are disturbed, patterned with shades of red.

*

The house in the Angel Wood seems to stretch forever back into the trees.

It had been an abandoned castle when my mother’s family first came here, but succeeding generations added to it without much thought for aesthetics. It is now a hybrid thing, with a tower of buttery grey stone, a white and brown E-shaped house sitting around it, and a variety of outbuildings that really belonged nowhere else. The outer walls are now tumbledown. The ancient green forest, Mother said, simply kept encroaching – whenever it was cleared away, it grew back as if nothing had happened, as if human will and action counted for naught.

Like puppies shut away for too long, we children tumble out into the late afternoon. My feet touch the earth and the ground seems to hum in welcome, a tremor passing through me. My blood dances in response, washing away the red of my dreams and any lingering distress. I belong here – I don’t know how I know this, but it comes to me with an undeniable certainty. This is my home and I will be welcome.

Jeremy-Charles takes faltering steps when I set him on his feet and the twins run almost to the entrance of the house. Mother swings down wearily from her perch, pulling hat from head, hair hanging stiff with a paste of sweat and road dust.

The door opens and what looks to be the oldest woman in the world hobbles out. She does not seem a witch, does not look malicious, merely older than anyone I have ever seen. Her skin is tanned and her hair such a white that it shines like mother-of-pearl. She is quite tall, not at all stooped, and she gives Mother a weary look.

‘Are you home, then? With all these?’ She jerks her chin toward us, her eyes catching the sun and flashing amber. I wonder who she is to speak to my mother so; none of our servants would ever have even considered a word out of place. ‘Where’s their father?’

I notice that she does not say your husband. Mother stoops to collect Jeremy-Charles, gasping as she straightens; I fear she is very tired. She faces the old woman, somewhat subdued.

‘Dead of the plague.’

‘And you thought to bring the contagion here?’ But she does not seem in the least bit fearful. I think she is afraid of nothing.

‘We are none of us sick, Agnes. I would not have come here otherwise, but I needed to get the children away. Where are my uncles?’ She looks beyond her adversary, as if expecting further welcomers.

‘Fenelon, George, and James are all dead. Old age, you see, and we’ve no young blood to continue on. We are much reduced, Susannah.’ She looks at us for a long moment, sighs and steps aside. ‘Come along. There’s plenty of room for you all.’

I am surprised by the amount of light inside; there are many windows, an expensive luxury at odds with the apparent shabbiness. Through the glass I can see the Wood; things flit from trunk to trunk in the shadows. Birds? Squirrels? I wonder if the house in the Angel Wood was like this when my mother left it or if it suffered for her leaving.

‘Do your offspring have names, Susannah?’

‘This is Henrietta-Henri. These are Millicent and Mathilda. The boy is Jeremy-Charles.’

‘How old are you, Henri?’ She addresses me directly.

‘Sixteen, madam.’ She is probably not a servant-or if she is, she is one of that strange breed who have no care for place or manners, and get away with it.

‘I’ll see to the horses,’ Susannah says-so much more Susannah than Mother now.

‘I will see to the children,’ Agnes answers, as if we, too, are animals to be fed and watered.

I take my brother from Susannah and she slips from the room. Jeremy-Charles insists on going to the old woman’s arms and I let him rather than risk screams. We tramp along to a large kitchen where fresh bread and yellow cheese are put out for us. We eat in silence until my curiosity gets the better of me.

‘Who are you?’

‘Agnes Woodville. I’m your grandmother.’ She pours milk for the girls and they happily slurp as if they’ve been ill-bred. ‘Your mother hasn’t told you about me?’

I shake my head. ‘I did not know she had any family until Father died and she said we would come here. She has never mentioned you before.’

‘No, I don’t suppose she would.’ Jeremy-Charles snuggles close to her as she feeds him bits of cheese. ‘She ran away from us. Married your father instead of staying here to do her duty by her family. She-’

‘Enough, Mother. Enough poison in my daughter’s ear.’ Mother stands in the doorway, pale and shaking.

‘When is truth poison, Susannah?’ Agnes asks. ‘If you stay they will know soon enough.’

‘For now, leave them be.’ Mother strokes my hair, red like hers. ‘Eat up, then we’ll find some bedrooms.’

Susannah sways, weary, and strangely bloodless. When she falls, her cloak opens to show a bright red stain on her white shirt.

*

I help carry Mother upstairs. She lies, pale as her pillows, while Agnes washes the wound. When my grandmother remembers I am still there, she sends me out. I am to find rooms for us, any that do not seem too full of dust, and put the children to bed. We will speak later.

I find an old nursery, with a huge bed and a cradle intricately carved and dark with age. Tildy and Milly think their new bed is a boat for sailing on the seas of sleep. I do not contradict them and bundle Jeremy-Charles into the crib where, presumably, generations of my mother’s family dreamt their earliest dreams.

Across the hall I chose a room with a four-poster hung about with green drapes and curtains. I am irrationally pleased to have a bedchamber to myself. In the city, I shared with the twins and, much though I love my little sisters, I am thoroughly sick of them stealing my ribbons, playing with my dresses, and leaving my books in a mess. The sturdy lock on the door brings a smile to my face as I turn the key, even though at this point I have no treasures to hide.

***