Kathleen’s art

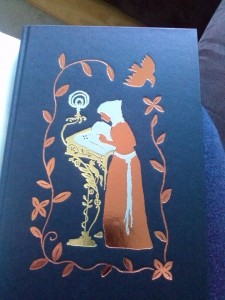

“The Bitterwood Bible” was always going to be an important story in this collection because it tells the history of the actual Bitterwood Bible and Murciana who made it. I’d given a lot of thought to Murciana because in Sourdough and Other Stories (the sequel to Bitterwood), she is referred to as Murcianus – indeed, there’s a whole library of books attributed to the almost-mythical-by-that-stage male author Murcianus. Even when I was writing Sourdough, I knew that that the usual kind of colonisation had occurred, that something created by a woman had been found to be so grand and widespread that it couldn’t be stamped out or eradicated … so it’s been appropriated and attributed to a man.

Throughout both collections there are a lot of magic books referred to and all are some version of Murciana’s Bitterwood Bible, even the grimoire used by Patience and Wynne Sykes in Sourdough (“Gallowberries” – and also in my soon-to-be-published Tor.com novella Of Sorrow and Such), known as Murcianus’ Book of Magica. One day I will write the tale of Sister Benedicte, who was tasked with copying the book and then stole it away. In this world there are all sorts of copies of this book, partial and full and annotated and extended … all to keep the knowledge in the world and all repurposed by their owners.

Kathleen’s art

I’d thought a lot about where Murciana came from and in the end it felt right to show how she arrived at the Citadel of Cwen’s Reach with the Little Sisters of St Florian. I could have started anywhere in her life, I suppose, even back to when she was the daughter of the vampires in “The Night Stair” (before they were vampires), but somehow showing her at the moment when she comes to the Citadel seemed right: she brought history with her, she was at a point where she might have decided to embrace terrible things, but instead she was offered a much better choice.

The Bitterwood Bible

All stories have a beginning, but beginnings themselves have many sparks, some slow to catch, others forest-fire fast.

Does this tale begin three hundred years ago, give or take, with the small child stolen from her parents? Does it begin the moment she ceases to cry for them, starts to forget them, loses her determination to find them again – for the best, really, so she will never know what they become? Does it begin when she is first ordered to pick up a quill, punished until she forms her letters correctly, beautifully? Does it begin when she starts to regard as hers the book in which she records everything for her master?

Or does it begin here, at the base of the cliff? At the breach through which only she can fit? Or in the tunnels that climb upward, honeycombing the substance of the promontory of Cwen’s Reach, upon which the Citadel sits?

Murciana’s palm is sweaty as she grips the torch, despite the glacial cold creeping through the tunnels. She makes dragon’s breath with every exhalation, and her lungs ache from the icy air she takes in. Beneath the soles of her shoes, the ground is a mix of rubble and rime, depending on how much seawater has flowed through. The passages are thin, in some places she must turn her scrawny self sideways to pass by – even if there’d been no other reason for her to undertake this mission, her master would never have fit through half these ways. She has to be careful with the satchel, adjusting it this way and that so its contents are not bumped and damaged.

Kathleen’s art

Her other hand is equally sweaty, wrapped as it is around the ivory hilt of the misericorde, which she holds ahead of herself. Her master offered the knife, casually at the very last minute – he has never let her near weapons before, certainly not handed her one – along with the advice that she might encounter some kinds of creatures in the tunnels, perchance large rats, smaller wild cats, mayhap even a troll or ogre – they liked dark places, although she shouldn’t worry too much as neither of the last three was overly fond of either sea or water. Oh, and she should look out for crevasses, subterranean lakes, uncertain earth and rock falls. With that he heaved her upwards and through the slim aperture, waiting only to pass the torch and dagger to her when her thin-wristed, ink-stained hand reappeared, questing for the light.

So far no crevasses, subterranean lakes, uncertain earth, nor rock falls. No large rats or even little ones, no smaller wild cats, nor troll nor ogre, although there had been times when she’d been certain of a stealthy footstep behind her, and she’d swung about, torch held high, blade jabbing at the dancing shadows. But there was nothing either mundane nor arcane trying to make itself known. She was alone, in the darkness, in the heart of a cliff, climbing upwards to ask questions of a thing of which she cannot quite conceive, although gods knew she’d seen enough miracles great and terrible in her short life.

‘It will only speak to you,’ her master had said as they’d trekked across marshlands and plains, through forests, up hill and over dale, until they came to that port city of Breakwater and negotiated passage to a small inlet half a day’s journey from Cwen’s Reach. Far enough away, he’d sworn, that they wouldn’t be noticed in the city of the Citadel. Another long walk along the ridges and clifftops, then down a rugged path and onto the sand and pebbles, struggling and stumbling until at last they came to the wide mouth of a cave. Inside the Magister cast a spell, throwing magelight across the damp dark space and searching until he found the ramp of scree that led up the hole in the rock wall.

‘It will only speak to another woman.’

‘That doesn’t mean it will speak to me,’ she said quite reasonably and was rewarded with a glare. ‘I only mean to say, Magister, that just because I’m female doesn’t guarantee its cooperation. What if it wants to know why I’m asking these questions? Why I’m copying down these spells? What do I plan to do with them? Surely saying “I shall give them into the hands of my master” will not be viewed well?’

She knew she was courting a beating, but couldn’t quite help herself, not even after all this time. She wondered that part of her refused to submit, to be obedient.

‘Just ask it the questions, and write down the answers. It won’t hurt you, but Gods help you if you return empty-handed.’

It seems she’d been climbing for hours, and in her mind she goes over the questions she must ask. They form a kind of rhythm for her footsteps, even as she worries at them, concerned that the word order will escape her – they must be spoken firmly, confidently, insisted the Magister, not read out. Aloud, she almost sings:

How to transform things for a season?

How to kill without trace?

How to live beyond one’s time?

She wonders if she might ask questions of her own? Would the Magister even know if she tried? After she’s asked his questions, obviously, those to which she must bring back answers.

Some while ago the sloping path had given way to steps, at first rough-hewn, but as she rose higher their craftsmanship grew, the precision of cut and placement increased, the materials changing from rock, to polished stone, to something that looked like marble and sparkled in the light from her torch. The walls grew smoother, the passages broadened, showing obvious signs of tool marks, of someone caring how this area looked. And soon enough she began to hear a low rumble, the timbre of a voice echoing in an enclosed space.

When she comes at last to a dead end, she reaches out and feels about, taking so long to find the catch that she thinks perhaps the Magister’s information had been incorrect. That she will have to go back through the winding underworld of the tunnels and bring him nothing after all his months and years of research and planning. That she will dash all his great hopes of finding what the tinker had told him was rumoured to be held in the deepest, most secret room of the Citadel. As she despairs, her fingers catch at it, the cold carven hook, which she pulls and feels it click.

There is a grinding, the painful sound of a mechanism unused for many years, and then the floor beneath her tips so she slips and is thrown forward into the space where the wall had been. She loses both knife and torch in the fall, and the bag lands heavily on her, knocking the wind from her. And she makes a noise, such a noise, with the dropping and the falling and the whumping.

Still and all, it doesn’t seem to bother the women watching her too much. Well, the woman and her companion, who is also female – looks female – but lacks everything except a head. The woman, the actual one, has half-risen from a low stone bench that encircles the basin where the other’s head floats on a sea of fire. Or is it cloud, all saffron-hued and red-streaked? On closer inspection, it is a kind of pond, not too deep, but filled with roiling, aggressive fire-clouds, yet the head does not bob, is not buffeted, simply levitates, hovering in the same spot, looking at Murciana with curiosity but not disdain, not fear. That gives the girl heart, which surprises her.

‘Good evening,’ says the woman in a low, rich voice.

‘Good evening,’ echoes the head, in an equally mellifluous tone.

Scrambling to her feet, readjusting the heavy satchel, Murciana manages to nod several times before she stutters out an appropriate greeting. All eyes turn to the torch which is guttering on the ground and the misericorde, whose thin blade seems blood-covered in the ruby light. Suddenly, Murciana feels unutterably rude – it isn’t a sensation with which she is too familiar, having not been trained in etiquette and having devoted large amounts of her time to perfecting a sly disrespect where the Magister is concerned. But before these women who’ve not batted an eyelid at her sudden arrival she feels callow and impolite.

***