I confess to a literary crush: I would walk miles over broken glass to get hold of the next John Connolly novel. The prose is pretty much pitch-perfect, the characters flawed, believeable, terrifying, engaging, witty and compelling. The dialogue – Connolly is one of the authors I look to for dialogue hints, to autopsy what he does and to analyse it so I can work out how it can be so damned good. But I begin to ramble.

I confess to a literary crush: I would walk miles over broken glass to get hold of the next John Connolly novel. The prose is pretty much pitch-perfect, the characters flawed, believeable, terrifying, engaging, witty and compelling. The dialogue – Connolly is one of the authors I look to for dialogue hints, to autopsy what he does and to analyse it so I can work out how it can be so damned good. But I begin to ramble.

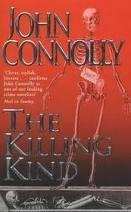

Connolly’s debut novel, Every Dead Thing, sparked a bidding war among publishing houses and won the SHamus Award for Best First Novel in 1999 – he may even have been the first non-American to win it – what him being Irish and all (someone correct me if I’m making things up – hey, I’m a writer, it’s what I do). Since then, his works have included further Charlie Parker novels (inlcuding The Killing Kind – not to be read by arachnophobes), The Book of Lost Things (about a young boy who has to negotiate a world inhabited by Old School fairytale characterrs – not the fluffy-sanitised-by-the-Grimms kind), the short story collection Nocturnes, and the stand-alone Bad Men. His latest is The Whisperers, which I banged on about here.

He was kind enough to answer five random questions:

1. You get to be any fictional character you like for a day, with no consequences: who do you choose, where do you go and what do you do?

Increasingly, as I get older, I feel that I’m coming to resemble Ignatius J. Reilly from John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces. I’m railing against the world more, and am showing a distressing inclination to read more non-fiction that fiction, so it can only be a matter of time before all I read is books about the glory of the Raj, and I begin making apologies for hardline right-wing dictators, and my children leave home because the collection of Nazi memorabilia in the basement keeps increasing, but only because I claim to be interested in the period. So, bearing that in mind, I’d have to go to New Orleans, and begin selling Paradise hot dogs from a vending cart.

2. You’re an Irish writer writing a very American character – have you ever, errr, stuffed up?

Oh, I still mess up occasionally, although thankfully most of my mistakes are caught by my copy editors. In the beginning, I struggled with the language a little, not just because there are different words for different objects, but because the rhythm of American speech is different from that of Irish speech. Now I’ve settled for a stylised version of the former that probably incorporates elements of the latter, and I make fewer mistakes. I have contacts for things like police procedures, guns, and material with which I might have struggled earlier on. I’ve never had somebody run over a hedgehog in California, though, as I understand one non-American writer once did. Mind you, when Americans write about Ireland and England they take some terrible liberties, and make some real howlers, so it’s not all one-way traffic.

3. I hate being a writer when …

I hate being a writer when taxi drivers ask me what I do for a living, and I’m dumb enough to answer that ‘I’m a writer’, and they ask me what I write, and I tell them, and they ask me would they have heard of any of my books, and I say that I don’t know, and they ask me for a title, and I give them one, and they shake their heads and tell me that they don’t recognise it, and then they ask me what my name is, and I tell them, and they shake their heads and tell me that they don’t recognise that either.

Now I just don’t tell taxi drivers what I do for a living.

4. Every Dead Thing is a complex novel, not only thematically, but structurally – do you ever look back on it now and marvel that you managed to pull it off in a debut novel? Think ‘Oh, my God, what was I thinking? How did I do that?’

I try not to look back too much at all, mainly because, like a nervous mountain climber, I’m afraid that if I look down I’ll fall. Structurally, Every Dead Thing has always had its critics because it’s structured like an hourglass, with one plot feeding through a narrow channel into another plot that is linked thematically, rather than directly, to the first plot. At the time, that was just how I wanted to write it, and as the initial chapters had already been rejected by just about every publisher everywhere I didn’t really feel beholden to anyone. Also, it took so many years to write that it was a bit like being lost in a forest for much of the time, and I have only very vague memories of how I got out. If I could change one thing about it, I would probably tone down some of the violence. It was more explicit in its descriptions than it needed to be, but I was a young author and I wanted people to understand how Parker could be so traumatised, and to give the reader a real sense of the nightmare world that the investigation forced him to inhabit. I’d like to think that I could do it more subtly now, but I might be wrong. It’s the curse of being a series writer: occasionally, a reader will come up and tell you that he or she still thinks that your first novel is the best, and you sigh and wonder if that means you’ve been going downhill ever since.

5. Donuts or danishes?

I prefer cinnamon buns, but if I had to pick one then donuts, although the idea of a donut is always more appealing than the reality. It’s a bit like Terry Pratchett points out in Going Postal: the smell of sausages cooking is always better than the actuality of the sausage.

His website is here and it’s worth a visit not only for the bonus short stories posted there.