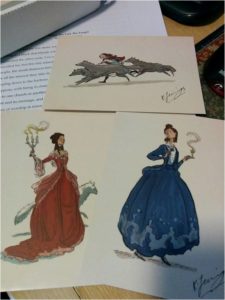

Art cards by Kathleen Jennings

So, I’m in a weird place at the moment, having delivered one series I’m not sure what (if anything) will be published next as far as novels are concerned. But I am working on finalising the first draft of this, Blackwater, something new for me, a gothic-y novel, set in Ireland and Australia. Here’s the opening chapter for those who are interested.

Part I: In All Beginnings, Are Endings

Chapter One

See this house perched not so far from the granite cliffs? Not so far from the promontory where the Howth lighthouse sits? It’s very fine, the house. It’s been here longer than the beacon, by a good few hundred years, and it’s less a house than a sort of castle now. Although perhaps “fortified mansion” describes it best. There are four towers, one at each corner, added in the mid-seventeen hundreds, and in between them an agglomeration of buildings of various vintages: the oldest, squarest, is a stone structure that was probably there first, a twelfth century thing, when the family first made enough money to better their circumstances. Two storeys and an attic, grey stone leeched by age; ivy grows over all it, except the windows, a strangely bright green almost like a sea algae, on the grey walls, winter and summer. Fourteenth century wings connect it to the towers; the age of the stables is anyone’s guess, but they’re a tumble-down affair, their state a nod to the family fortunes perhaps. There is stone that’s sometimes grey, sometimes gold, sometimes white, depending on the time of year, time of day and how much sun is about, and embedded in the walls are swathes of glass both clear and coloured from when the O’Malleys could afford the best of everything; the glass lets the light in, but cannot keep the cold out, so the hearth are enormous, big enough for a man to stand upright or an ox to roast in.

They built close to the cliffs – but not too close, they were wise the first O’Malleys – so there’s a broad lawn of green, a low wall almost at the edge to keep all but the most determined, the most stupid, from toppling over, and there’s a path that winds back and forth on itself, an easy trail down to a pebbled shingle that stretches in a crescent. At the furtherest end is a sea cave, or was before the collapse, a tidal thing you don’t want to be caught in at the wrong time. A place the unwary have gone looking for treasure for rumours abounded that the O’Malleys smuggled, committed piracy, hid their ill-gotten gains down there until they could be safely shifted elsewhere and exchanged for gold and silver to line the family’s already overflowing coffers.

The truth is, no one knows where they came from but no one can remember a time when they weren’t here, or at least spoken of. No one says ‘Before the O’Malleys’ for good reason; their history is murky, and that’s not a little to do with their very own efforts. Local recounting claims they appeared in the 1100s, perhaps in the vanguard of Strongbow’s army, or perhaps trailing along behind gathering what they could while no one noticed, until they had enough to make a reputation. What’s spoken of is that they were tall even in a place where the Norse raiders had liberally scattered their seed, but not blond: dark haired, dark eyed, with skin so terribly pale that in another country folk might mutter that they didn’t go about by day, but that wouldn’t have been true.

They took the land by Howth Head and built the first house; they prospered quickly. They built ships and traded, and built more ships and traded more, roamed further. They grew rich from the sea and everyone knew tell of how the O’Malleys did not lose themselves to the water, they their ships did not sink and their sons did not drown (or only those meant to) for they swam like seals, learned to do so from their first breath, first step, first stroke. They kept to themselves, seldom taking wives or husbands who weren’t of their extended families – they bred like rabbits, but the core of the family remained tightly wound around a limited bloodline. And they paid no more than a passing care for the opinion of the Holy Mother Church, which was more than enough to set them apart, make them an object of unease and rumour.

But they kept their position. They were neither stupid nor fearful. They cultivated friends in the highest of high places, sowed favours and reaped the rewards of doing so, and they gathered secrets and lies, oh! such a harvest. The O’Malleys knew the locations of all the inconvenient bodies that had been buried due to exigence; sometimes they put the bodies there themselves. They paid their own debts, made sure they collected what was theirs, and ensured all who dealt with them knew that what was owed, would be paid back one way or another.

They were careful and clever.

Even the princes of the church found themselves, at one point and other, beholding to them. Some churchman of import required a favour only the O’Malleys could provide and so, hat in hand, he came to them. Under cover of darkness, of course, in a closed carriage with no regalia that might give him away, on the loneliest roads out of Dublin to the big old house on Howth Head; he’d take a deep breath as he stepped from the conveyance, then another as he looked up at the great panes of glass lit from within so it looked like the interior was on fire, and he’d cross himself for fear that he might find himself somewhere more infernal when he crossed the threshold.

More than one made such visits over many years. Yet such men mislike owing favours to anyone – especially women – and there was a time when females held the O’Malley family reins; those very same priests tried to avoid paying one debt or another. All manner of excuses offered and an equal number of threats and coercions too. None of them worked, and the ecclesiastics found themselves brought to heel: a bishop was unseated and moved on like some common mendicant, and the smile on the lips of the matriarch wide and red.

And it’s a loss that’s never been forgotten, not in several hundred years, and it’s unlikely to ever be. Indeed, the Church’s memory is long and unsleeping, and in each successive generation one of her sons has sought a way to make the family pay. No matter that the O’Malleys had given a child to the church for as long as anyone can recall, that they paid more than their tithes required, and they supported endowed livings for more than one cleric, gave charitably to many causes, and had a pew with their name on it in St Patrick’s all to themselves, where they sat every Sunday whenever in attendance at the townhouse they maintained in Dublin.

An insult once given to the Holy Mother Church is never forgotten, though the family had grown too influential to be easily destroyed, and generations of godly men have devoted a good deal of their lives to ill-wishing the O’Malleys past, present, and future. Much effort and energy were devoted to the cursing of the name, gossiping about the source of their prosperity, and plotting to take it from them. Many was the head shaken in rue that pyres and pokers were no longer options available as a means of enforcing conformity.

But it wasn’t only the more godly members of Dublin society at odds with the O’Malleys. Though they were generous, those who took O’Malley charity often found that the price attached to the aid rendered was much higher than they could have imagined. Some paid it willingly and were rewarded for the family valued loyalty; those who complained were justly requited. As time went on business partners thought twice about joining O’Malley ventures, and the more cynical amongst them counted their fingers twice after shaking hands on a deal, just to make sure all their digits were intact. Those who married in to the extended branches did so at their peril, for many were the husbands and wives deemed to be untrustworthy or simply inconvenient when passion had run its course, and disposed of quietly. And their dealings were always quiet, but things done ill always leave echoes and stains behind. Because they’d been around for so very long, the O’Malleys’ sins built up, year upon year, decade upon decade, century upon century.

There was something not quite right with the O’Malleys, they didn’t fear like others of their ilk; they, perhaps, put their faith elsewhere. Some said the O’Malleys had too much salt water in their veins to be good Catholics, or anything else good for that matter. But nothing could be proven, not ever, not in almost eight hundred years.

As it turned out, they brought themselves down without aid from the Church.

They’d not been bothered, or not overly so for the decline had seemed gradual, at least at first. Their ships began to sink or be taken by pirates; then investments, seemingly shrewd, were soon proven unwise. It was, although no one but they knew, their bloodline that had faltered first, and their fortunes followed soon after.

Almost all their affluence bled away, faster and faster, until within a generation there was just the house on the promontory (the Dublin townhouse having been sold to a lesser branch of the family); the great fleet was whittled was to a couple of merchant vessels making desultory journeys across the seas; and the deeds to some property in the Americas, the value of which no one was quite certain. The O’Malleys had too many debts, too little capital, blood running thin …

The grounds of the grand mansion were once carefully tended by an army of gardeners, but now there’s only a single man – Malachi who is ancient, barely breathing, farting dust – to take care of things. All the walled gardens are over-run – all but one, the one the old woman uses – their doors bound shut with brambles. The paths through are maintained but only just, and those who walk them risk having sleeves and skirts torn by thorns and branches, twigs with too much length and strength. Malachi’s sister, Maura – younger and less given to farting – does what she can to keep the interior of the house shining, but she’s one woman, arthritic and tired and cross; it’s a losing battle.

And now there’s just a single daughter left of the household, whose surname wasn’t even O’Malley because her mother had committed the triple sins of being the only surviving child of four, a girl, and insisting from sheer perversity on taking her husband’s name, despite her own mother’s insistence that it really should be the other way around. Worse still: he had no O’Malley lineage, this Liam Elliott, so the daughter’s blood was thinned once again.

And in this, the Year of Our Lord 1896, the family found itself much diminished in more ways than one. Unable to pay its creditors and investors, unable to give to the sea what it was owed, and with too few of other people’s secrets to use as currency, the O’Malleys were, at last, in danger of extinction.

***