1. What do new readers need to know about J. Ashley-Smith?

1. What do new readers need to know about J. Ashley-Smith?

I’m a British–Australian writer of dark – often speculative – fiction.

I’m not in any way nationalistic or even particularly patriotic, either to my new or my old home country (fingers crossed that ASIO/MI5 aren’t reading this interview). Still, I always seem to lead my answer to that question with where I’ve come from and where I am now – perhaps because it gives some insight into my status as outsider, wherever I find myself. Even though I’ve lived in Australia for approaching 15 years, I still feel out of place, as though I stepped through a portal into some weird parallel universe. Now, even Old Blighty, when viewed through this lens, seems unrecognisable and unfamiliar.

That kind of wrongness and disorientation, the sense of everyday things just out of true, is something that obsesses me. Another obsession is that inner dark from which the fantastic, the terrifying, and the impossible are born. The collision between the complexities of the modern day-to-day and the invisible or imagined world is another fixation, which I continually explore in my stories.

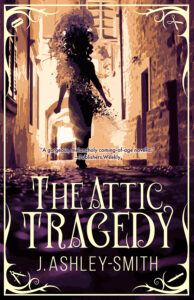

2. What was the inspiration for The Attic Tragedy?

The Attic Tragedy was born from three separate, inanimate ideas that rattled around inside me for two or three years before striking together and sparking a story. The first was the setting, the second was a dream, and the third was a rather cheap pun stolen from Nietzsche’s first book: The Birth of Tragedy.

Antique shops and attics hold a strange fascination for me – as I’m sure they do for many people. They are mysterious places, full of forgotten things, like storehouses for the discorporate memories of every object’s past owners. As a child I was obsessed with attics, my parents’ attic in particular, and always wanted to go up there to rummage around, certain I was going to discover some lost thing destined to lead me on a fantastic adventure (reading between the lines, you may be able to tell that I was a lonely, imaginative sort of boy). The Blue Mountains, where the story is set, is full of antique shops. We had just moved from the mountains when I started the story, so perhaps that was what triggered it.

I won’t go into the details of the dream – other people’s dreams are incredibly tedious, no matter how surreal or revelatory they were for the dreamer. This particular dream involved a girl who could speak with ghosts. She was going to a ‘specialist’ – a sort of medical exorcist – for an operation to cut off her connection to the spirit world.

Finally, the pun. I was reading The Birth of Tragedy as research for a novella I was writing at the time (Ariadne, I Love You, coming out from Meerkat Press next year). Throughout, Nietzsche refers to ‘Attic tragedy’, meaning Greek tragedy, but I loved the images that came to mind when I muddled the meaning and the title sort of stuck.

Of course, none of these elements on their own is much of a story. And even put together they were only a half-living thing. It was the character of George, who emerged in the process of writing, that really brought the story to life for me and made it the thing it is now.

3. When did you first know you wanted to be a writer?

I first started imagining myself as a writer around the age of ten or eleven. At that time, I hadn’t really made the connection between being a writer and actually writing.

I was a next-level daydreamer throughout my childhood (and, frankly, to this day), and a vivid night-dreamer. My head was always full of stories. Mostly, though, it was just wool gathering. I did write a few actual stories at that age, but I didn’t start identifying as a writer who writes until I was on my way to university. By then I was a card-carrying, chin-stroking, wannabe beatnik, hiding out in the corners of cafes hoping I looked deep. Scribbling mind-rubbish onto a legal pad, then, was de rigueur.

I didn’t learn to actually finish stories until about six years ago. That was around the same time the stories I wrote started getting published. (Doubtless a coincidence.)

4. Can you remember the first story you ever wrote?

Back when I was about ten or eleven, I had a hideout in what we called “the cellar,” which was really the foundations of our house. Underneath the downstairs floorboards an alternate version of the house was carved. A cramped space, with a floor of concrete dust and brick shards, somewhere between two and three feet from the ground to the floorboards. It was entirely dark and mimicked the layout of the rooms above, with crawl-spaces knocked into the brick walls. I had a camping mattress and some blankets down there, and used to lie about reading 80s Stephen King novels: Carrie, The Stand, Salem’s Lot.

I’m going in to all this (what some might argue is extraneous) detail, because the description of this den, the memory of it – close and dank, faintly redolent of mildew – is so intertwined with the first story I remember writing. I wrote it in a hardback A4 journal with a buff cover, the inside pages closely lined. The story itself was little more than a few paragraphs, and took up only about a third of one page, but it was extremely gory. It was about a woman who threw salt over her shoulder, so enraging the Devil that he dragged her straight to Hell and horribly disembowelled her. There wasn’t much in the way of a narrative arc. It was, however, VERY descriptive.

Not long after that, I heard what I thought was a body dragging itself across the rubble in the next ‘room’ of the under-house. I fled the den with my heart in my throat and have not been down there since.

5. Who are your main literary influences?

The answer to this question would be different depending on when you asked it. My influences have shifted over time and new inspirations emerge whenever I’m immersed in a project, trying to find a particular tone or approach. Rather than swamp you with my life story in literary heroes, I’ll go with the two most prominent and consistent for me recently, going back about the last five years or so.

The first is – perhaps predictably – Shirley Jackson. I came very late to her work, but fell into it like a lover’s embrace. The first book of hers that I read was The Haunting of Hill House and, reading it, I felt I had come home – not to Hill House, of course, but to Jackson’s way of viewing the world, and particularly the supernatural. In all of her stories that I have read, what’s in the foreground is the people, all their psychological complexities painted with such a deft and subtle brush. The weirdness is everywhere, but it’s in the background, found only in the gestalt and not in any one or other element. The supernatural is ever present, but always uncertain. Throughout Hill House, the reader is never entirely sure whether the haunting is ‘real’ in any measurable sense – it is both real and, at the same time, only in the minds of those who perceive it. And the characters through all of her books and stories are just wonderfully unusual, wonderfully real: Eleanor and Theo; Merricat and Constance Blackwood, Uncle Julian; Eleanor, from my favourite of her short stories, The Intoxicated. I could go on, but will have to rein myself in, before I start to rave sycophantically…

The other author currently in the ‘Where have you been all my life?’ category is Patricia Highsmith. I was struggling to make sense of a novel I have been drafting and redrafting for several years, trying to understand what in the hell sort of book it even was. Reading Strangers on a Train blew me away, and made me see immediately what I was supposed to be trying to achieve with my own book – and all the ways in which I was nowhere near achieving it. The fact that Highsmith wrote Strangers in her late twenties never ceases to nauseate me. And that she then followed it up with so many unique and extraordinary classics: The Blunderer; Deep Water; This Sweet Sickness; and, of course, the books for which she is most famous, the five novels covering the life of Tom Ripley, affectionately known as ‘The Ripliad’. No author has held so transparent a lens to the horrors of suburban psychopathy, or portrayed the crimes of the everyday with such clarity and brutality. Finding Patricia Highsmith was, for me, like tripping down a bottomless well. Her work is so bleak, so searingly perceptive, and she is so damn prolific – it’s a deep well.

6. You get to take five books when you are exiled to a desert island: which ones are they?

I’ve thought about this one long and hard. If I was truly exiled, there are very few books that would bear a lifetime’s repeat reading. I’ve gone here for a mix of practicality and longevity – by which I mean, I’ve probably taken this question way too seriously!

- The SAS Survival Handbook

- Field Guide of Tropical Reef Fish

- Complete Poems of Walt Whitman

- The Odyssey (Ancient Greek version)

- Ancient Greek to English dictionary

Books 4 and 5 could just as easily be: Crime & Punishment, and a Russian/English dictionary; or Journey to the West, and a Mandarin/English dictionary; or [insert very long book written in a language not my own, plus the means to slowly translate said book over many, many years].

I hope I’d be left some pens and paper, too. Or would I have to get handy with seagull quills, squid ink and dried palm leaves?

7. Who’s your favourite villain in fiction?

As a rule, I tend to be more interested in stories where the characters possess a certain moral ambiguity, rather than the cut and dry hero vs villain type of narratives. I like not being able to rely on characters to do what I want them to do – or for them to be doomed always to do the things they shouldn’t.

Having said that, there are certain antagonists who scare the willies off me. I was watching the new series of Dark recently, which has three villains who are particularly creepy. I’m not going to talk about them – this isn’t a question about TV – so no need to worry about spoilers. Rather, they are a jumping-off point for a particular kind of psychopath in fiction that I find most terrifying – they are embodiments of some archetypal darkness or violence, precisely because their motives are incomprehensible and somehow outside of reason.

In Cormac McCarthy’s novel, The Outer Dark, there is a trio of ‘bad men’ who seem to embody the horror that lurks just beyond that borderline between civilisation and the seething chaos beneath. I get similarly freaked by the character Pozzo, in Beckett’s Waiting For Godot, who enters the play like some monstrosity from The Road, with his slave jester in tow.

And don’t get me started on …

8. Person you would most like to collaborate with?

I expect I’d be a terrible collaborator. One of the things that drew me to writing – after studying and making films at uni, followed by a decade or more in bands – was the degree to which I could have control over everything. I’m still coming to terms with my own way of doing things, so can’t imagine getting back into that collaborative mindset with this, my last bastion of creative control.

Having said that, I’m not opposed to it. But I can’t think of anyone off the top of my head.

9. What’s next for J. Ashley-Smith?

Did I mention I have another novella coming out from Meerkat Press in 2021? And there’s a short or two coming out this year, including a novelette, The Black Massive, about teenage ravers who fall in with an eldritch crowd. That’s coming out in October, in the final (sobs) issue of Dimension6.

I’m also on the home stretch of a suburban suspense novel I’ve been writing on and off for the last few years – imagine if Patricia Highsmith had written Lord of the Flies. It’s set on an Australian beach holiday and is about an eleven-year-old sociopath coming into her full power. I hope to have it wrapped by the end of the year – but I’ve been saying that every year since 2016, so…

Bio:

Ashley Smith is a British–Australian writer of dark fiction and other materials. His short stories have twice won national competitions and been shortlisted six times for Aurealis Awards, winning both Best Horror (Old Growth, 2017) and Best Fantasy (The Further Shore, 2018). His debut novelette, The Attic Tragedy, is out now from Meerkat Press. He lives with his wife and two sons in the suburbs of North Canberra, gathering moth dust, tormented by the desolation of telegraph wires.

You can connect with J. at spooktapes.net, or on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.