Alas, a Rackham will have to do.

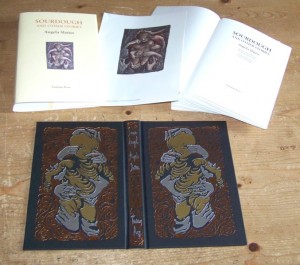

So, I’ve been sort of missing writing about The Bitterwood Bible and Other Recountings and I thought ‘Why not give Sourdough and Other Stories the same treatment?’ Alas, I haz no Kathleen art for this collection (but my evil plan is to one day have a omnibus collection of all three books, all with Kathleen’s drawings *steeples fingers*).

It’s a while since I’ve really thought about these stories except in so far as how they related to the writing of The Tallow-Wife and Other Tales, so I decided to revisit them. They become particularly interesting when you realise that The Tallow-Wife will finish off the cycle of the Sourdough stories and it will also bring the character Ella, who makes her first appearance in “The Shadow Tree” and gets several mentions in Bitterwood, to her own end.

When I started this story I had the phrase ‘nigra sum sed formosa’ in my mind – again, I’d been reading Eco’s The Name of the Rose and it was one of the phrases that stuck with me. I’d been thinking about exiles and home and family, and what family might find unforgivable, and I’d also been reading Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market and Angela Carter’s “The Erl-King”, as well as various versions of robber bridegroom tales. I thought about governesses and nursery maids, the sort of people left in charge of other people’s children and thought about how you can never be certain who or what you’ve brought into your home. I wondered what a character might do to find her way back to a home she’d thoughtlessly left and now missed more than life itself.

And thus was born Ella, with her darkness and her desires, her dislikes and her sense of putting things right in a fairly dreadful way.

The Shadow Tree

Original art by Stephen J. Clark

‘Why are you so dark, Ella?’ squeals Brunhilde, the king’s daughter. She is thirteen years old. It is the fourth time she has asked me the question since she and her brother invaded my rooms this afternoon. They are both verminous brats, exactly the kind I seek. The other one, the youngest, is not out of swaddling cloth so I cannot yet judge him. Sometimes it is simply enough to leave them to do harm where they may.

‘Yes, Ella. Why so dark? Do you roll in the dirt at night or sleep in the cinders?’ Baldur is fourteen and equals his sister in unpleasantness, occasionally surpassing her. Platinum blonde hair and violet-blue eyes, they are shining, flawed metal, the worst that a

royal house can offer: cruel, spiteful, selfish, beautiful, utterly confident of their position in life.

‘Nigra sum sed formosa,’ I answer, pleased at the blank stares they give. ‘Does your tutor not teach you Latin, then?’ I click my tongue, a gesture both despairing and scornful. I do not translate that I am dark but comely. ‘Ignorant children, what a blot upon the world.’

Brunhilde throws herself at me, and hangs off my skirt, trying to tear the fabric. If she had eyes and mind to see beyond the ordinary, she would notice that the material was fine once, a heavy brocade embroidered with gold and silver thread. The filaments are so aged and dull now their shine is lost to all but the most observant. She begins a chant and will not stop. ‘Why, why, why, why, why, why?’

‘Shut up, Brunhilde.’ Baldur sometimes sees further than his sister, sometimes he tries to dig. She drops away, sits on the cold floor and sulks. ‘You do not know your place, Ella.’

‘My place is here for the moment, for as long as I choose,’ I say. I do not mention that warming their father’s bed now and then gives me licence to say what I please—within measure. My position as herbalist gives me power, too. I supply the physician with the medicines upon which his reputation rests. Ladies of the court come to me for unguents to keep their skin soft, or for drafts to get rid of inconvenient pregnancies. The Queen occasionally asks for something to make her husband sleep and so relieve her of his demands for a night or two. Men want love philtres to help them do their best by their womenfolk, or to make them eloquent before the King. The Archbishop, Serenus, comes more often than most. I have been here six months, threading my way through the life of the palace and this little city of Lodellan, which thinks itself large. Soon it will be time to go.

‘You do not speak like a servant. You do not behave like a servant.’

‘Yet I am a servant,’ I finish curtly. ‘Now, get out of my room, and take your squalling sibling with you.’

‘You cannot order us about!’ squeaks Brunhilde.

‘I can and have. Now out, or there will be no stories tonight, nor for a sennight to come.’ Here is my real power over them: the tales I tell. They have become small addicts, to our sessions and the drops of mandrake I put in their milk. The nights when I am not telling their father fables of a different sort, I spend beside their beds, recounting myths and legends to take into their dreams. Even though the children are vile, this weaving of words is a pleasure for me, and it furthers my ends. I suffer no illusions: they do not love me. As long as I provide an amusement, it will stave off the moment when they turn on me.

‘Not like the one you told last night, Ella,’ Baldur says warily. I shake my head, hide my smile. I gave them the history of the Erl-King and in the morning they both woke with tears on their cheeks.

‘No, I’ll tell you something exciting, something secret,’ I promise.

When they have gone, I unlock the door to my workroom and step inside. A thin cat detaches herself from the shadows under one of the benches. She glides around my skirts, mews to be gathered up. She’s black, with the greenest of eyes, tiny and frail still. I rescued her from the children a month ago; they were tormenting her in the stables, had already executed her kittens and dangled their limp bodies in front of her. For a long while, the cat wouldn’t eat, but eventually I coaxed milk into her mouth and loved her into living. She is gentle and sad. For their efforts, Brunhilde and Baldur spent two weeks vomiting and shitting, fed with one of my potions, and their sheets sprinkled with a compound that made them break out in red, itching spots.

The cat’s face against mine is warm and she is soft in my hands. I hold her like a child, and survey the room. It is dim because some of the plants and powders I work with do not like the light. It smells musty, but layered with sweetness and something bitter and dark at the very base, like rotted roses. In the end, it reminds me of home, a comfort and an ache at the same time, to remember a place and an exile from it.

Hesitantly, I uncover the mirror that waits in one corner. It’s big enough to show my face and torso, faded dress, cat in arms. My skin is deep olive, burnt by the sun as I tramp the hills beyond the forest for herbs, my face an oval set with dark eyes and an unbalanced mouth—upper lip thin, the lower full. My brows are straight, and my hair as black as the cat’s fur. I have the look of a gypsy, a wanderer.

I wonder if perhaps my time has passed and I can return. In hope, I touch the glass, feel it cool under my fingertips, wish that I could travel through it, through the doors between worlds, back to my own place. My exile isn’t yet done. The surface remains hard, unbroken, impenetrable. The cat makes a soft noise, like sympathy. I bury my face in her fur.

***