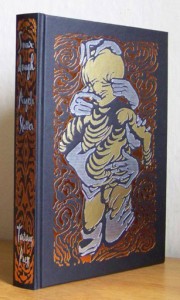

Kathleen’s drawing from Bitterwood’s “Spells for Coming Forth by Daylight” – works well here too.

“The Story of Ink” follows on from “Ash” in that it traces the fate of the baby Blodwen gave away in the earlier story. Her life isn’t the wonderful dream the poor witch imaged for her, but she’s got a kind of freedom for a while at least. But this story isn’t told by her, it’s told by very young Livilla (who later appears as a grown-up in “Sister, Sister”). Like Blodwen, she’s working for a powerful man, a prince of the church, with an interest in matters less ecclesiastical and more arcane.

I like Livilla; she’s a study in the lies we tell ourselves in order to do things we’re not proud of, things that, ultimately, break our hearts forever no matter what we might later do to atone.

The Story of Ink

The girl is thin, flat-chested and badly dressed, but her hair is dark and glossy and her cheekbones high. Her skin is clear and glowing. The torn sleeve of her dress shows the tiny red flash on her shoulder I’ve been told to look for – get closer, he said and it will be a tiny red crown. She’s easy to recognise, all things considered. The old man’s daughter, a runaway.

He’s paying; I’ve got instructions; he says she’s his daughter, so she’s his daughter.

I watch a while longer, the better to know my quarry. She laughs and jokes with the stall-holders in the market and the other whores – these girls work the streets, they’ve not got the protection of one of the pleasure inns. This isn’t the fancy market at Busynothings Alley. It’s just as busy but nowhere near as clean, nor as reputable. This is Half-moon Lane, out in the slums, out where people live packed on top of one another, where the truly desperate find a home in the sewers and crypts. Some even live in the hollows at the base of the city walls.

Strictly speaking, it’s far too wide for a lane, more like an avenue or a boulevard but, well, there you go. In Half-moon Lane you can buy the usual bits of food and spice, pots and pans, but there are also potions and poisons to be had. If it’s an assassin you’re after then try any of the taverns that line the pavement, and if it’s love you’re in need of and don’t want to pay the over-heads of an inn-bred whore, then Half-moon Lane will fulfil your requirements. Girls just as pretty but cheaper, and with a shared room at the top of one of the perilous staircases that cling to the sides of the buildings. Just watch out for the pimps, that’s all.

How this pampered girl came to be here is a mystery. You can see she’s had a soft start in life, it shines through whatever’s happened to her on the streets. But almost everything else is as the old man said it would be. Almost. What I didn’t expect, what he didn’t tell me, probably didn’t know, is what she’s carrying: a baby, wrapped in ragged but clean blue cloth. A boy if tradition’s anything to go by, maybe a year old.

I rap my cane on the roof of the carriage and the driver knows to gee-up the horses and  pull us over to the other side of the lane, stopping just near the girl. Pennyworth gets down and opens the door, unravelling the fine metal steps so I can descend.

pull us over to the other side of the lane, stopping just near the girl. Pennyworth gets down and opens the door, unravelling the fine metal steps so I can descend.

Around me the noise stops and I’m pleased with the effect I have. My outfit is cut like a riding habit, although I’ve never been on a horse in my life. Blue velvet the same shade as my eyes, the short jacket is fitted and detailed with silver braid; the skirt is full and falls like water. Around my wrist is a pearl bracelet and on my right index finger, a silver ring, filigreed with a moonstone setting. I love the tricorn hat that perches on my dark red curls. The silver-topped cane I clutch in my right hand was a fine gift from my employer. (He said I should be protected and showed me how to slide the blade out from the bottom section.) The fact that I’m only eleven completes the strength of the impression I make.

I take small precise paces toward the girl, holding my skirts so they won’t drag in the mess and muss. She watches me, the corner of her mouth lifting in amusement. There’s nothing unkind in it, but it annoys me, that she doesn’t take me seriously. My outfit, my poise, my position were all hard won and here’s this street-whore laughing at me.

I taste the acid of resentment, but I paste a smile on my face. No point in showing her what I feel. You catch more flies with honey than vinegar, my old mum used to say, when she was sober enough to say anything.

‘What’s your name, lovely?’ I ask and her grin lifts into a full smile. She really is beautiful.

‘Jessamyn, but for a quarter-gold it can be whatever you like,’ she laughs to let me know she’s joking. She jiggles the baby on her hip and looks at me amiably. ‘You’re a little young for my services, darling.’

‘I make you a proposition on behalf of my master,’ I tell her, lifting my hands in a magnanimous gesture, the cane twirling in the fingers of one hand, then hopping across to the other. I’m still thinking, trying to figure out what to offer her, what will tip the odds in my favour.

‘Indeed? And what does he offer, this man who sends a child into the streets?’ Her face displays distaste now and I can’t help myself.

‘What I do I do willingly. Don’t be fooled by my size, missy. I choose to be here and I am no man’s whore,’ I hiss, showing more of myself than I would like. She recoils and looks ashamed, to have shown herself judging of me when she’s the one walking the streets, some stray get on her hip.

‘I’m sorry,’ she says and I can tell she is. ‘Let’s start again, shall we? I’m Jessamyn.’

I take a deep, calming breath and smile brightly. ‘And I’m Livilla. My master asks that you come to visit. Perhaps that you will stay, if you find his house and company agreeable.’

‘And how does your master know me?’ The baby’s fat little hands curl around her fingers and she gives him a distracted smile. How hard is her life with this one to keep? But she has not let him go like so many of them do. She did not get rid of him by drinking some witch’s brew. She keeps him close; that should tell me something about her.

‘He has driven by in his carriage.’ I gesture over my shoulder at the fine black conveyance with its silver trappings, but conspicuously lacking a coats-of-arms or any device that might mark it out. ‘He’s an important man, is my master, and it wouldn’t do for him to be seen approaching a woman on the street …’

‘So he sent you?’ she says and gives a laugh. The baby giggles, too, hearing her. He grabs a handful of her lush black hair and gently plays with it. I wonder what my master will do with this grandson of his. Farm him out? Send him to one of the orphanages? Keep him at home and hold him close? I cannot tell.

‘Just come and see. One visit. A good hot meal for the boy-bee. Nice bath for you. I’ll look after the little bloke. Nothing too strenuous, for my master is venerable.’

‘Isn’t venerable just a big word for old?’ she asks, all mirth.

I ignore her and go on, ‘Just one visit and if you like it then think about staying. Better to be in one of the fancy houses. Better to raise the boy in a safe place, to let him be educated by tutors, rather than thieves. What do you want him to grow up to be? Honest man with a good trade, or a pickpocket?’

Her eyes darken. The boy rubs his face against her neck like a puppy seeking a pat. She runs a hand over him as if to check that he’s not too thin, not too deprived. He’s a fat happy baby, but I don’t tell her that; don’t offer reassurance.

‘Alright,’ she says.

I smile, trying to simply look pleased and not triumphant, as if this is a happy result for both of us. As if this won’t bring me a longed-for reward. A little place of my own, one of the tiny townhouses that border the richer cantons, newly built for the newly respectable in the row that burnt down last year in a conveniently tidy way (a most controlled conflagration, it has been noted). A little house over four floors and no one to share it with, new-fangled plumbing and tiny a little garden out the front. All my own.

Pennyworth’s waited by the coach all this time, now he bows politely as I usher the ragamuffin in and follow her quickly. I flutter my lashes at him and he knows to lock the door after he rolls up the steps. The door on the other side of the coach has been long ago fused shut.

Inside we rest on velvet red seats, comfortably firm, but soft to touch. We both sit so as to face forward when the carriage moves. In the middle of the seatback is a panel and I slide it smoothly out. A small tray with a crystal decanter and two glasses sit in their own little case. Some freshly-made sweetmeats wait in a crystal dish suspended in a kind of silver cage. I know they’re laced with an opiate, so even though they make my mouth water I cannot have one. Although, perhaps, for later, when I need to sleep, I will take one.

I pour her a drink and she accepts it graciously, nodding to me over the rim of the glass. The baby tries to grab at it and she gently shushes him. He whimpers but settles. I break off a corner of a sweetmeat and push it into his mouth; it will calm him if nothing else. I offer her a fresh piece but she shakes her head.

Stephen J. Clark’s cover art

‘I prefer apples. Lost my taste for sweetmeats after I gorged myself sick on them once,’ she says and I curse inwardly. The tokay isn’t drugged – the old man insisted she would take the sweetmeats, so he didn’t drug the alcohol, so I could drink it too and not raise suspicions if I insisted she drink alone.

She lifts one of the shades and looks out the window. She goes pale; she must recognise the way we’re going.

‘No,’ she says. ‘No!’

‘C’mon, love, I’m taking you home,’ I say, trying to sound sympathetic, but it doesn’t seem to help. Her eyes go wide and she’s panicking, but she still doesn’t hit me. That’s the advantage, I guess, of being a kid. She tries the door on her side and finds the handle useless, then pushes past me to get to my door, but it’s locked too.

‘You don’t understand. You don’t know what he’s like.’

‘Come now, calm down. He’s your dad and he just wants you to come home. Be a family, like.’ I twist the top of the ring and the little spike pops up. I grab for her arm and scratch the skin, carving a thin furrow that wells red. She yelps but it doesn’t take long for the poison to work. I have to grab the baby from her so she doesn’t drop him as she falls into a deep, drugged sleep.

***