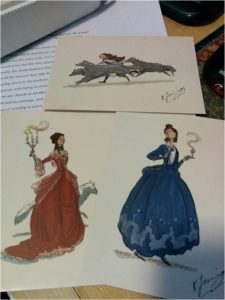

As always art by Kathleen Jennings coz wolves and candlesticks and pouffy skirts …

So, I spent most of last year and the first few months of this year working on a novel called Blackwater. It’s a gothic fantasy set in the same world as the Sourdough and Bitterwood mosaics, and I thought I would share the first chapter with you. Hopefully more news on this next week …

Chapter One

See this house perched not so far from the granite cliffs? Not so far from the promontory where once a church was built? It’s very fine, the house. It’s been here a long time (far longer than the church, both before and after), and it’s less a house really than a sort of castle now. Perhaps “fortified mansion” describes it best, an agglomeration of buildings of various vintages: the oldest is a square tower from when the family first made enough money to better their circumstances. Four storeys, an attic and a cellar in the middle of which is a deep, broad well. You might think it to supply the house in times of siege, but the liquid is salty and part way down, below the water level, you can see (if you squint hard by the light of a lantern) the silver crisscross of a grid to keep things out or in. It’s always been off-limits to the children of the house, no matter that its wall is high, far higher than a child could accidentally tip over.

The tower’s stone – sometimes grey, sometimes gold, sometimes white, depending on the time of year, time of day and how much sun is about – is covered by ivy of a strangely bright green, winter and summer. To the left and right are wings added later, suites and bedrooms to accommodate the increasingly large family. The birth date of the stables is anyone’s guess, but they’re a tumbledown affair, their state perhaps a nod to lately decaying fortunes.

Embedded in the walls are swathes of glass both clear and coloured from when the O’Malleys could afford the best of everything. It lets the light in, but cannot keep the cold out, so the hearths throughout are enormous, big enough for a man to stand upright or an ox to roast in. Mostly now, however, the fireplaces remain unlit and the dormitory wings are empty of all but dust and memories; only three suites remain inhabited, and one attic room.

They built close to the cliffs – but not too close for they were wise the first O’Malleys, they knew how voracious the sea could be, how it might eat even the rocks if given a chance – so there are broad lawns of green, a low wall almost at the edge to keep all but the most determined, the most stupid, from toppling over. Stand on the stoop of the tower’s iron-banded door (shaped and engraved to look like ropes and sailors’ knots). Look ahead and you can see straight out to sea; turn to right but a little and there’s Breakwater in the distance, seemingly so tiny from here. There’s a path, too, winding back and forth on itself, an easy trail down to a pebbled shingle that stretches in a crescent. At the furtherest end is a sea cave (or was before a collapse, the date of which no one can recall), a tidal thing you don’t want to be caught in at the wrong time. A place the unwary have gone looking for treasure as rumours abounded that the O’Malleys smuggled, committed piracy, hid their ill-gotten gains there until they could be safely shifted elsewhere and exchanged for gold to line the family’s already overflowing coffers.

They’ve been here a long time, the O’Malleys, and the truth is that no one knows where they were before. Equally no one can remember when they weren’t around, or at least spoken of. No one says “Before the O’Malleys” for good reason; their history is murky, and that’s not a little to do with their very own efforts. Local recounting claims they appeared in the vanguard of some lord or lady’s army, or one of those produced by the battle abbeys in the days of the Church’s more intense militancy, perhaps one marching to or from the cathedral-city of Lodellan when its monarchs fought for land and riches. Perhaps they were soldiers or perhaps they trailed along behind like camp-followers and scavengers, gathering what they could while no one noticed, until they had enough to make a reputation.

What is spoken of is that they were unusually tall even in a place where long-legged raiders from across the oceans had liberally scattered their seed. They were dark haired and dark eyed, yet with skin so terribly pale that on occasion it was muttered that the O’Malleys didn’t go about by day, but that wasn’t true.

They took the land by Hob’s Hallow and built their tower; they prospered quickly. They took more land, they gained tenants to work the land for them. There was always silver, too, in their coffers, the purest and brightest though they’d tell no one from whence it came. Next they built ships and began trading, then built more ships and traded more, roamed further. They grew rich from the seas and everyone heard tell of how the O’Malleys did not lose themselves to the water: their galleons and caravels, their barques and brigs did not sink. Their daughters and sons did not drown (or only those meant to) for they swam like seals, learned to do so from their first breath, first step, first stroke. They kept to themselves, seldom taking wives or husbands who weren’t of their extended families. They bred like rabbits, but the core of them remained tightly wound around a limited bloodline; those bearing the O’Malley name proper were prouder than all the rest.

They paid nought but a passing care for the opinion of the church and its princes, which was more than enough to set them apart from other fine families, and made them an object of unease and rumour. Yet they kept their position and their power. They were neither stupid nor fearful. They cultivated friends in the highest of high places, sowed favours and reaped the rewards of doing so, and they gathered secrets and lies from the lowest of low places. Oh! such a harvest. The O’Malleys knew the locations of all the inconvenient bodies that had been buried – sometimes purely because they’d put the bodies there themselves. They paid their own debts, made sure they collected what was theirs, and ensured all who dealt with them knew that what was owed would be returned to them one way or another.

They were careful and clever.

Even the greatest of the god-hounds found themselves, at one point and other, beholding to them. Sometimes an ecclesiastic of import required a favour only the O’Malleys could provide and so, hat in hand, he came. Under cover of darkness, of course, in a closed carriage with no regalia that might give him away, on the loneliest roads out of Breakwater to the mansion on Hob’s Hallow. He’d take a deep breath as he stepped from the conveyance, then another as he looked up at the lofty panes of glass lit from within so it seemed the interior of the tower was on fire. He’d clasp the golden crucifix suspended at his waist for fear that, upon crossing the threshold, he might find himself somewhere more infernal than expected.

More than one such man made visits over many years. Yet such men mislike owing favours to anyone – especially women and there was a time when females held the O’Malley family reins – and those very same priests offered all manner of excuses, threats and coercions trying to avoid their obligations. None of them worked, and the brethren found themselves brought to heel each and every time: an archbishop or other lordly cleric was unseated and moved on like some common mendicant, and the smile on the lips of the matriarch was wide and red.

It was the sort of loss – an outrage – that had never been forgotten, not in several hundred years, and it was unlikely to ever be. Indeed, the church’s memory is long and unsleeping, and in each successive generation one of its sons at least has sought a way to make the family pay. No matter that the O’Malleys had given a child to the church for as long as anyone could recall, that they paid more than their tithes required, and maintained several almshouses in the city. They even had a pew with their name on it in Breakwater’s cathedral where they sat every Sunday whenever in attendance at the townhouse they maintained in one of the fancier districts.

An insult once given to the church was never forgotten nor forgiven, and generations of godly men had devoted a good deal of their lives to ill-wishing the O’Malleys past, present, and future. Much effort and energy were consecrated to the cursing of the name, gossiping about the source of their prosperity, and plotting to take it from them. Many was the head shaken in rue that pyres and pokers were not options available as a means of enforcing conformity in this particular instance – the webs woven by the clan were too strong to be evaded or undermined.

It wasn’t only the more godly members of Breakwater society at odds with those who lived out on Hob’s Hallow. Those who took O’Malley charity or made good-faith bargains with them often found that the cost was much higher than could have been imagined. Some paid it willingly and were rewarded for their loyalty; those who complained or baulked were justly requited. As time went on business partners thought twice about joining O’Malley ventures, and the more cynical counted their fingers twice after shaking hands on a deal, just to make sure all digits remained. Those who married in – whether to the extended branches or the main – did so at their peril. More than a few husbands and wives were deemed untrustworthy or simply inconvenient when passion had run its course, and disposed of quietly.

There was something not quite right with the O’Malleys, they didn’t fear like others of their ilk. They, perhaps, put their faith elsewhere. Some said the O’Malleys had too much salt water in their veins to be good and god-fearing, or good anything else for that matter. But nothing could be proven, not ever.

Their dealings were discreet, but things done ill always leave echoes and stains behind. Because they’d been around for so very long, the O’Malleys’ sins built up, year upon year, decade upon decade, century upon century. Life upon life, death upon death.

The family was simply too influential to be easily destroyed but, as it turned out, they brought themselves down with neither aid nor agitation from either church or peers.

It was their bloodline that had faltered first – although no one but they knew – and their fortunes followed soon after. Fewer and fewer children were born to the O’Malleys proper, but for a while they’d not been bothered, or not overly so, for seemed like nothing more than a brief aberration. Besides, the extended families continued to multiply, and to prosper financially.

Then their ships began to sink or be taken by pirates; then investments, seemingly shrewd, were quickly proven unwise. The great fleet was whittled down to a couple of merchant vessels making desultory journeys across the seas. Almost all their affluence bled away, faster and faster until within a few generations there was just the grand mess of a home on Hob’s Hallow. There were rumours of jewellery, silver and gems buried beneath the rolling lawns – no one could believe it was all gone – but the O’Malleys had too many debts, too little capital, and their blood was running thin …

And so the family found itself much diminished in more ways than one. Unable to pay its creditors and investors, unable to give to the sea what it was owed, and with too few of other people’s secrets to use as currency, the O’Malleys were, at last, in danger of extinction.

The estate was once carefully tended by an army of gardeners and groundsmen, but now there’s only ancient Malachi – barely breathing, regularly farting dust – to take care of things. All the walled gardens are over-run, to enter them would be to risk having sleeves and skirts torn by thorns and branches with too much length and strength, and besides, their doors are sewn shut with brambles. All but one that is, the one the old woman – the last true O’Malley – uses when she seeks fresh air and solitude. In the house, Malachi’s sister, Maura – younger by a little and less given to farting – does what she can to keep the gilings and decay at bay, but she’s one woman, arthritic and tired and cross; it’s a losing battle, though she keeps her hand in with herb magic and rituals to keep the kitchen garden producing vegetables and the orchard fruiting. There are two horses to pull a rickety calash; three cows, all almost beyond giving milk; several chickens whose lives are likely to be short if they do not begin to take their duties more seriously. Once, there was an army of tenants who could be called upon to work the fields, but now they are few and the land has laid fallow for a very long time indeed. The great house is decaying and the great curved gates at the entrance to the estate have not been closed in a decade for fear any movement will tear them from their rusted hinges.

There’s just a single daughter left of the household, whose surname isn’t even O’Malley, her mother having committed the multiple sins of being an only child, a girl, insisting from sheer perversity on taking her husband’s name, and then dying without producing further offspring. Worse still: this husband had no O’Malley lineage – not a drop – so the daughter’s blood was thinned once again. She’s twenty-one, this girl, a woman really, raised mostly in isolation, taught to run a house as if this one isn’t a ruin waiting to fall, with a dying family (decreased yet again by a recent death), no fortune, and no prospects of which to speak.

There’s an old woman, though, with plans and plots of long gestation; and there’s the sea, which will have her due, come hell or high water; and there are secrets and lies which never stay buried forever.

***