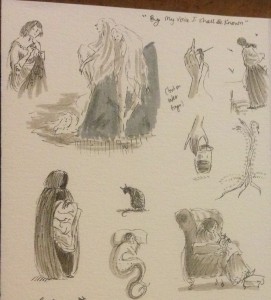

Sketches by Kathleen Jennings for By My Voice I Shall Be Known

In “By My Voice I Shall Be Known” I wanted to combine elements that contained echoes of stories about the Lorelei Rock, the rusalkas, and Melusine, all wrapped up with a traditional kind of betrayal and revenge tale. The title comes, I think, from something I read about one of the Sybils … but unfortunately I can’t quite remember which one and I don’t seem to have kept a note about it. Bad writer. But I love the idea of that ringing sound, that bold statement that her voice will be all she needs … even though it’s been taken from her.

My mother is a quilter and I find what she does absolutely fascinating and very beautiful – yet I’m not a person with any talent for crafting thing with my hands, so it does seem a kind of witchcraft to me. When I was writing, I remembered a comment by my friend, Alan Baxter, who’d said that watching his wife knit was like watching folk magic happen – and I thought that quilting was pretty much like that too.

You’re creating something to cover you at night, a protection from cold, mozzies, and monsters (it really is!) – why wouldn’t it be magical? I thought further about the idea of glory boxes that young women used to prepare for their marriages – why wouldn’t they want a thing to bring them good luck, a prosperous and happy future? Something to cover their marriage bed? Maybe even something that might influence a husband’s behaviour? And what if the magic could be made to work in different ways?

By My Voice I Shall Be Known

If I still had a voice, I would cry out.

The fabric is thick and my needle blunt – I should have sharpened it before now – so I put too much weight behind my thrust and forced the point. Not only the quilt, but also my finger is impaled. I do not wail, though I long to, determined not to make the hideous grunt that is the only noise left to me. In my memory, I still hold the sound of my voice, but each time I bellow it lessens, chips away at the timbre so lovingly preserved in recollection. Slowly, carefully, I draw the thread fully through, then pull my injured digit off the silver shaft. A scrap of spare cloth is wrapped around the glistening blue-ruby drop, then the needle itself is assiduously cleaned. I set the bulky bundle of material aside and limp, my legs stiff from hours of sitting, to the basin in the far corner of the tiny room Mother Magnus has given me. Washing the injury, applying a salve, then bandaging the deep wound; I look out the window, not really seeing so much as remembering what is there before me.

Bellsholm sprawls along the banks of the wide Bell River, loose-limbed as a sleeping giant;  a rough crescent with its northern tip truncated by the bulk of the Singing Rock. In the foothills that hug the edge of the town some few ramshackle houses have crept, not too high, and certainly nothing up on the majestic outcropping of the promontory. At the furtherest boundaries there are farms to supply the markets and businesses best located away from the centre of town, such as the carriage maker, the foundry, the marble worker’s studio, three carpentry and joinery firms, and Ballantyne’s Coffin Emporium where the strange woman employs four apprentices and, rumour has it, keeps a locked room filled entirely with mirrors. There is also the hostelry, where travellers with no interest in the hamlet can rest, eat, exchange their tired horses for fresh ones, then continue their journeys. Down by the river are the docks, brimming and bobbing with great ships from afar filled with all the finest things a prosperous place requires, and small local boats that bring in fish and travel up and down the reaches too narrow for the caravels and barques.

a rough crescent with its northern tip truncated by the bulk of the Singing Rock. In the foothills that hug the edge of the town some few ramshackle houses have crept, not too high, and certainly nothing up on the majestic outcropping of the promontory. At the furtherest boundaries there are farms to supply the markets and businesses best located away from the centre of town, such as the carriage maker, the foundry, the marble worker’s studio, three carpentry and joinery firms, and Ballantyne’s Coffin Emporium where the strange woman employs four apprentices and, rumour has it, keeps a locked room filled entirely with mirrors. There is also the hostelry, where travellers with no interest in the hamlet can rest, eat, exchange their tired horses for fresh ones, then continue their journeys. Down by the river are the docks, brimming and bobbing with great ships from afar filled with all the finest things a prosperous place requires, and small local boats that bring in fish and travel up and down the reaches too narrow for the caravels and barques.

I can hear, dimly, the melodies of the rusalky, wafting up from the base of the Rock, where they laze daily (except Sundays when the sound of church bells sends them into hiding) and serenade anyone who will listen. Murdered maidens, those unfortunate in love, gather their spirits to sit on the rocks, dangling luminescent toes in the water. The weak of will may traipse too close and fall in. Some drown. The natives are, by now, mostly inured to the strains and are all brought up to swim like eels – indeed, Léolin will tell you that as a young man only his strong stroke saved him on the day when he was distracted by a particularly lovely ballad. The greatest danger is to travellers, on ships and on the roads, unfamiliar with our ladies.

***